IV. War on Crack (1986-89)

Note: section 4 is one of the almost-finished sections of this exhibit (along with section 1) but is still in development and should not be cited or quoted or reproduced without contacting mlassite@umich.edu first. The data on police homicides in this section is also incomplete.

“We're at an important crossroad in our Nation-the awareness that drug abuse is now epidemic and at the same time that an even deadlier drug is now available for consumption. That drug is crack, and it's sweeping across our country like a tidal wave. It's inexpensive and highly depressive, our young people are using it in all of our metropolitan areas, and our police and law enforcement people are asking us what we are doing about educating our young people about the dangers of this new deadly drug”

-Congressman Benjamin Gilman, 1986

In the mid-1980s, the United States took part in a major legislative and ideological shift from a generalized War on Drug to specific targeting of crack cocaine. Policies that once stressed large-scale drug networks and international influence began to focus more heavily on local and street-level crime as their primary threat. As the narrative of a crack “epidemic” heightened perceptions of drugs plaguing all pillars of society, federal funding for anti-drug programs, specifically those under the rule of law enforcement, increased dramatically. Inner-cities like Detroit bore the brunt of the increased militarization of law enforcement, with programs such as Operation Crack Crime eliciting a significant increase in violent drug raids and arrests in specifically targeted areas. The rising fears of the dangers of crack and the devastation that it produces influenced the shift towards policies becoming increasingly more punitive through federal legislation, especially in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986’s creation of mandatory minimum sentences and policies that favored incarceration over rehabilitation.

While the policies themselves originated from federal power, the community concern over narcotics-related issues garnered tremendous support for many of these initiatives, with local organizations calling for greater policing to rid their neighborhoods of crime and drugs. While law enforcement efforts were largely viewed as necessary by both politicians and citizens, the image of cleansing the streets of dangerous dealers and criminal gangs did not quite materialize in an idealized way as the line of criminality became increasingly blurred. Discretionary policing — law enforcement left to the interpretation of officers — intensified in urban settings, as the fear of failing to eradicate cities from an overdramatized threat of criminal behavior overshadowed respect for civil liberties, specifically those of minorities. Though it may have appeared that Detroit’s progressive Mayor Coleman Young’s attempts to diversify and reform the force would have curbed injustices, the reality did not meet the expectation for substantial change.

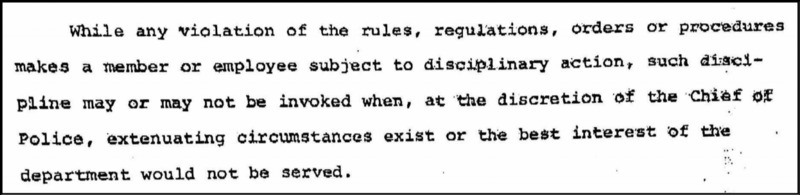

Policing trends in the mid to late 1980s shifted from incredibly localized street policing to a national investment in specialized tactical forces, SWAT-like raids, and an overall militarization of local police forces. This coupled with increases in discretionary policing on the basis of race and social class led to an increase in police assaults, murders, and invasions into the homes of certain targeted civilians. Street-level stop-and-frisk policies that were prominent in years prior prevailed as well, with a Detroit Police Department manual from 1987 stating that officers need only “reasonable suspicion” that someone may commit a crime in order to search them. While there were some rules in place surrounding the practice, it was made clear that officers would not necessarily be reprimanded for going against protocol, if disciplinary action didn’t serve “the best interest of the department”. However, police, legislators, and media outlets were able to justify this escalation of discrimination and force using the dialogue of the “crack epidemic”- which became the general excuse for vicious, and often illegal, behavior, and thus led enforcement efforts increasing aggregate violence as opposed to reducing it.

Sensationalization of the War on Crack in Media

The film New Jack City is based on the types of high-operation, corporate drug rings that took over the Metro Detroit area in the 1980s. Two examples of the New Jack City concept in Detroit are the two notable drug gangs that, for various years in 1980s Metro Detroit, monopolized the drug market in Detroit and utilized a corporate structure to maintain a strict, regulated business model: Young Boys, Incorporated and the Chambers Brothers Drug Network. This type of drug gang, with enforced hierarchy and employee rules, was an entirely different version of drug running from what the Detroit Police Department had dealt with in the past. The utilization by these gangs of young Black men looking for upward socioeconomic mobility was a facet of 1980s drug culture. Police were often tasked with raiding suspected crack dens and very frequently arrested these young “runners,” dismantling the entire networks took years of police strategy and tactical operations, much of which involved heightened police violence and brutality in the neighborhoods that these networks supplied.

While these gangs did exist and were incredibly prevalent in Detroit during this time, the national attitude towards drugs created a political climate that encouraged fear, outrage, and outcry for police involvement across cities in the United States. Hip-hop music became intrinsically linked to drug and gang culture, and agencies like police departments and local governments capitalized upon this correlation to further criminalize Black youth. Markers for drug gangs were broadened to fit youth of color that listened to certain artists, wore certain colored clothes, ansd hung out in certain neighborhoods. The scourge of drugs was a nearly universal fear among community members in both urban and suburban environments -- but urban areas were those considered dangerous and ridden with drug pushers praying upon suburban youths. The inherent racial and socioeconomic implications of the mythologies that emerged in the 1980s due to drug-related media are vast and outside the scope of this project; but they are still prevalent today and worth viewing with a critical, questioning eye.

Corruption in the Force

Police misconduct in this time period manifested often in brutality and homicide against civilians, shifting slightly during this time period to take place more often in or around the home or vehicle as opposed to primarily occurring during incidents of street policing. Trends in police homicide may have shifted after 1985 due to the Tennessee v. Garner decision which made it illegal to shoot a suspect while they fled. Otherwise, the trickle-down of national drug policy had direct effects upon Detroit police interactions with civilians. The passage of the 1986 Anti Drug Abuse Act reallocated money from federal funds to each state to combat drug use and distribution. This came into play in Michigan not just in Detroit, which was its largest metropolitan population center, but also in smaller towns across the state. The difference in the implementation of the 1986 ADA is that in suburban, primarily white towns is that much of this new funding was allocated toward drug education as opposed to policing and drug-based incarceration. Sweeping increases in mandatory minimum laws and harsher sentencing laws hit Detroit immediately in the wake of the ADA, along with a distinctive change in police practices across low-income and primarily minority precinct districts in Detroit. The DPD’s investment into tactical squads and SWAT-like divisions, especially in certain low-income areas tagged for drugs and gangs, contributed to a heightened presence of policing the home. Brutality occurred in both street policing and in the homes of people raided by SWAT teams; increased discretionary policing allowed police to monitor areas more closely and act in ways that they deemed acceptable without the levels of supervision that one would encounter in a non-drug ridden or wealthier area.

Misconduct is further exhibited in the prevalence of drug usage in the DPD and drug-related extortion became a major facet of police culture and conduct. With the emergence of crack cocaine in Detroit streets, it became apparent that DPD officers were using and abusing the drug at an increasing rate as the War on Crack progressed. Reports of on-duty and off-duty officers exhibiting erratic and often dangerous behavior flooded the office of DPD Chief William Hart. Additionally, the news media caught onto the DPD's drug problem in multiple scathing article series across the late 1980s. This being said, Detroit cops were profiting off of established systems and mechanisms within Detroit’s criminal justice system that kept them from being charged and indicted in misconduct, brutality, and homicide cases. Only a fraction of incidents went to court against police officers, and out of that fraction only a small amount were given publicity or reported on. Drug-related crime was not limited to use and distribution; drug charges, because of the extreme nature of sentencing laws for a small amount of drugs, were easy to falsify should the police be able to plant a small amount of marijuana, crack, or other controlled substances on the suspect. There are some instances wherein this is reported, but there is no existing metric to try and account for all of the false charges that have been brought against Detroit citizens for drug possession.

Historical and Archival Silences

Through the research and findings presented in this exhibit, it is important to acknowledge the reality of limitations that exist in this type of investigation. Historical archives are a tremendous source of information and discovery, but gaps in data and documents exist due to the nature of how these sites acquire their materials. In many cases, the information that is sought after may no longer exist, or remains hidden in an unknown location. For this reason, uncovering the entirety of this story is unfortunately impractical. Newspaper resources similarly house a wealth of knowledge, but are further subject to the biases of sources and reporters. Reporters are responsible for deciding which stories are notable enough for publication, meaning that many events go untold. While this exhibit has identified 10 police homicides and 20 occurrences of police brutality or mistreatment of civilians, based on historical data trends, this is likely only a fraction (estimated at about a quarter) of incidents that truly ensued.

What is so vital about acknowledging the historical silences that we have encountered through the research process is that these are often illustrative, if not symptomatic, of the shifts in the culture surrounding reports of police misconduct. As police became more militarized and corruption in the force became more evident and more public via media coverage and officer conduct, it is probable that widespread disillusionment regarding the police led to fewer and fewer reports filed about misconduct. This is just one of many possible sociological explanations for the decrease in reports we found from previous years; as the War on Drugs escalated (and more specifically, the War on Crack), militarization and de-localization of police could have very well led to a disconnect in communication between civilians and their local officers, despite the narrative of a united front. Another possible explanation is a lack of faith in the recourse a person would be granted should they choose to fill out a report against a police officer; with Mayor Coleman Young’s administration in its last few years, a sense of complacency in regard to police brutality and misconduct is a possible reason for collective disinterest in filing disciplinary reports against DPD officers.