Use of Force Study

“The failure of the Detroit Police Department to discipline its officers is intentional and deliberately indifferent to the rights of the citizens.” -Clinton Donaldson, DPD Commander of Internal Affairs

Causes

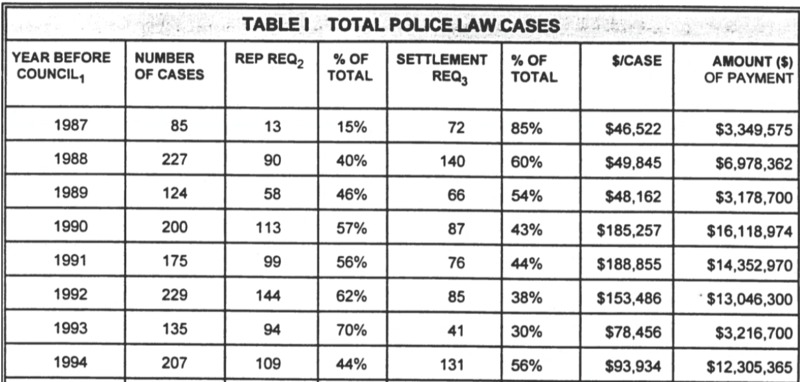

By the end of 1993, the public’s reaction to police violence signaled to the Detroit Police Department that they had to take action. Before taking action, the DPD conducted an intra-department study on its officers’ use of force during citizen confrontations. The study focused on the instances of reported police violence from 1987-1990. The total number of complaints documented by the DPD during this period was 1,079 and these complaints against officers were evaluated by their peers. In order to be considered guilty, the citizen making the complaint was expected to be undoubtedly trustworthy and the officer was thought to have acted explicitly inappropriately. As a result, disciplinary action was taken in only 91 instances and in 92% of the cases, the officer was not found guilty of any offense. Armed with knowledge of this information and statistics about the rising number of cost of lawsuits against the city, specifically DPD, citizens protested police violence and demanded a change. However, these sentiments were decades old, and the primary reason for the 1993 Use of Force Study was the exceedingly expensive lawsuits filed against the City of Detroit.

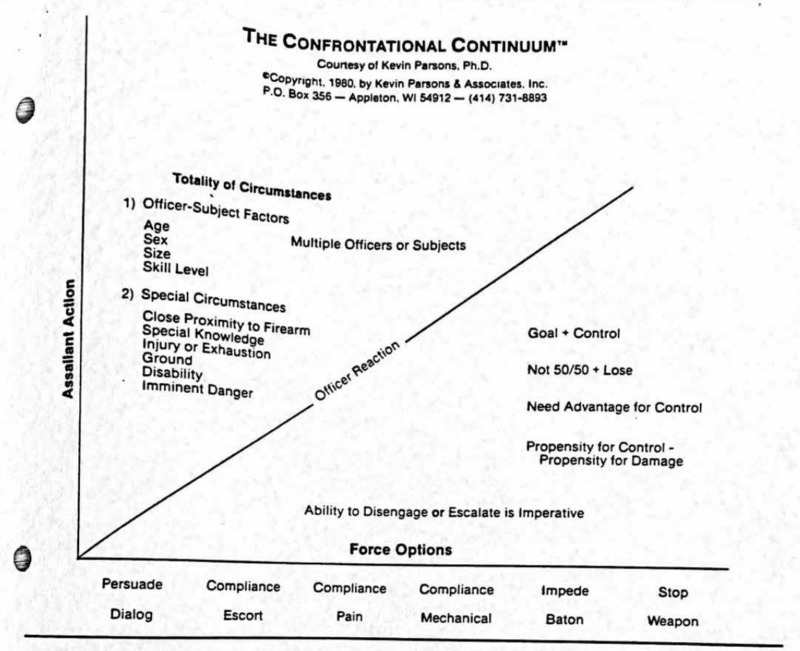

The existing use of force policy in Detroit was recognized to have flaws in an Inter-Office Memorandum circulated in 1993. The policy is said to have had a continuum that ranged from verbal commands to physical control, but the sergeant who wrote the memorandum acknowledged the need for more methods to deescalate and prevent criminal activity. Sergeant Blount’s recommendation was the introduction of chemical spray, commonly known as pepper spray or mace, but not without a considerable amount of training for officers issued it. One of his major arguments for its implementation was “a significant decrease in liability exposure.”

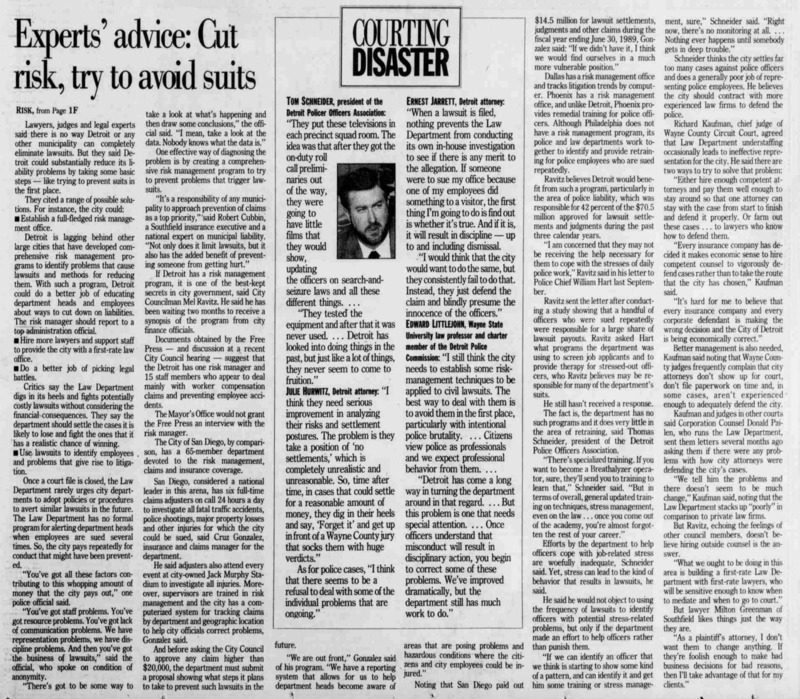

Lawsuits against police officers and the City of Detroit had reached a peak in the late 80s and early 90s. This trend was documented in a series in the Detroit Free Press called “Courting Disasters” in the summer of 1990. The media investigation revealed that there was no system for identifying what officers had been sued on multiple occasions and that there was no formal training for officers that emphasized how to properly use force. From 1987 until 1989, the City of Detroit paid out $70.5 million in lawsuits, and police lawsuits accounted for 40% of this number. City Councilwoman Barbara-Rose Collins expressed frustration at the lack of cooperation from the Board of Police Commissioners. She claimed that “For over eight years, I’ve been asking the Police Department to give us information on what they’ve done with police officers found at fault. They never give it to us.” In part of coverage, both Mel Ravitz and DPD officers claimed that stress was a primary reason for the behavior that resulted in lawsuits. This claim is clearly a coverup for the systematic causes of police violence in Detroit, as the Free Press even compares Detroit to San Diego, where lawsuits were much less prevalent, but they did not mention anything about police stress in San Diego. An officer stated that “he would not object to using the frequency of lawsuits to identify officers with potential stress-related problems, but only if the department made an effort to help officers rather than punish them.” This is a direct plea to the Board of Police Commissioners and the DPD to not hold officers who had committed crimes accountable. This same officer cited poor representation for officers as a reason for the high payouts of lawsuits. The true cause of the lawsuits were police officers who exhibited violent behavior repeatedly, knowing that they would not be punished.

On May 10, 1993, Officer Samuel D. Braxton wrote to Mayor Coleman Young regarding the lack of responsibility of those in command at the DPD. He expressed frustration at the lack of punishment for officers that had used excessive force, claiming that "other officers who were found guilty of serious violations often receive a slap on the wrist..." He also claimed that there was not enough being done to prevent excessive force in the department. Braxton expressed his concern with the lack of training on how to use non-lethal force, which echoes the concerns of many Detroit citizens. He then stated his intention to resign from the force because of the lack of responsibility from the leaders of the DPD. Instances of violence, recognized even inside the department itself, had ushered in the need for a new approach to the use of force.

Outcomes

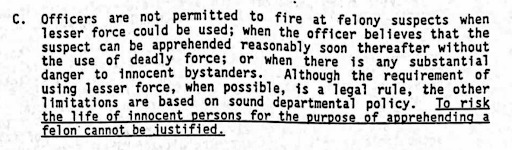

As a result of the study, the Detroit Police Department planned on implementing new regulations about the use of force against citizens. The suggestions for the DPD were based largely on what they considered the “ideal police department,” the Kansas City Police Department. The above images are excerpts from the KCPD’s “Use of Force Policy.” In a letter from Harold C. Scott of Internal Affairs in the DPD, he admired the way the KCPD is specific and precise about their policies and houses all of the information about the topic in one document. Other aspects of the KCPD’s policy that he praises are their extensive training on which kind of force is most likely to result in injury, how to use communication to avoid physical confrontation, and the explicit instructions they use for disciplining officers.

In addition to making changes based on the KCPD model, the use of chemical spray, or what is commonly known as “pepper spray” or mace was introduced to the DPD after this study. Pepper spray was thought to be an important tool in the use of force continuum because it would not permanently harm civilians, yet it could protect the safety of officers. In the May 1993 edition of The Police Chief, Sergeant Bruce Anest of the Phoenix Police Department stated that “you’ll find yourself going from verbal commands to pain compliance to deadly force because you have nothing in between.” This was true of the DPD before the introduction of pepper spray and served as an important argument for its use. Police Chief Stanley Knox remarked that the only non-lethal weapon officers carried was a baton, which often inflicted physical injuries on civilians. An inter-office memorandum from Sergeant Michael Blount echoed this sentiment, adding that “nor have there been any lawsuits associated with the use of OC spray.” A clear objective of the DPD is to avoid costly lawsuits, which should not be prioritized before protecting citizens and treating them with respect. The reasons he states for the use of chemical spray range from life-threatening to when someone is passively resisting arrest. It should be mentioned that he requested that officers be properly trained in its use. In the summer of 1994, the DPD implemented the training and use of chemical spray.

In the wake of the Malice Green murder and trial along with the Rodney King beating in Los Angeles, flashlights came under examination as a form of lethal weapon. The heavy metal flashlights that officers typically carried were intended to provide light at night or in dark places, but they were clearly being misused. An inter-office memorandum from 1993 cites seven allegations of police misuse of flashlights in the year before Green’s death and four allegations in the following year. A decrease of three allegations is insignificant and still indicates the improper use of flashlights even following the highly publicized incident. An executive meeting of the DPD focused solely on the use of metal flashlights. Clinton Donaldson, the Commander of the Internal Controls Division, shared information about a presentation on using flashlights as a weapon in Massachusetts and the group of officers decided to implement plastic flashlights. Importantly, the minutes from the meeting state that “It is imperative that our efforts concentrate on decreasing officer prosecutions both criminally and departmentally.” To correct the systematic corruption of the DPD, it should have been imperative that the safety and wellbeing of citizens was prioritized. It further states that the use of metal flashlights was not a new issue, but when the DPD had originally contemplated purchasing plastic flashlights, they declined because the cost would be $10,000. The officer writing the minutes then laments that the city has to spend $10 million on litigations from the Green case instead of just having spent the $10,000 in 1990. An advertisement for a lightweight flashlight found in the Coleman Young Papers is evidence of the brutality of police flashlight abuse.

From the research we conducted, it is only evident that the DPD changed its policy in written form and implemented the use of chemical spray and lightweight flashlights. There did not seem to be evidence of any other systemic changes, but information about the results of the study were difficult to uncover in the archives. The cause of this is unknown, but we hypothesize that there were not many impactful changes made, so there was no paperwork to document the study’s results. What was confirmed to have changed, however, appeared to be meant to keep officers out of trouble rather than keep officers from getting into trouble. Officers who had abused civilians with flashlights now physically could not, but they were not trained in other ways to prevent encounters from becoming violent. Instead of shooting civilians, officers could maim them temporarily with pepper spray. These new tools did not teach offers to be less violent; they only prevented officers from being punished for subduing civilians with physical force.

Sources used for this page:

Coleman Young Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Detroit Free Press, July 15, 1990.

Detroit Police Office Annual Report 1990