The War On Black Youth

Unintentional Effects of Community Policing

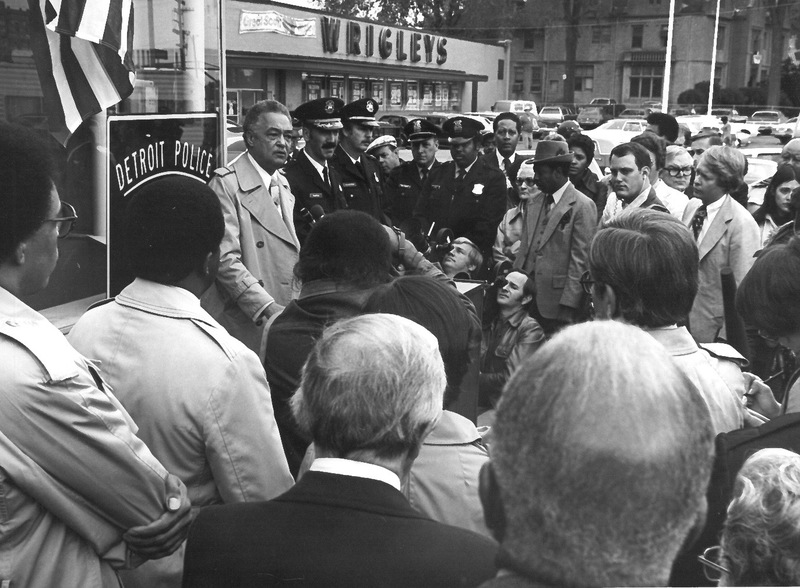

Coleman Young, in line with the larger national trend, advocated for community policing. In Detroit, this took form in celebrating neighborhood watch efforts and most notably the invention of the Ministation. There were also increased efforts to expand the use of scooter patrols in order to have a well-distributed police presence in the community and programs that sought to engage the youth. The programming coincided with heavy affirmative action recruitment efforts. The premise is founded on a theory that increased community involvement in policing would heal police-community relations. Instead, criminalization and the subsequent violence against Black people became inescapable. Black communities were overpoliced while simultaneously all citizens were encouraged to engage in “policing” by looking out for, and reporting “crime”. There was particular paranoia around the drug market and the complaint office received many anonymous alleged “dope-house” tips. While the complainant may feel their call made the community safer, it often resulted in a violent, heavily armed, and random raid of a home.

The combination of fear mongering in the media around crime and the call for community policing effectively created police out of the community. During this time, police were also introduced into schools, which we now source as the beginning of the public school to prison pipeline that tracks the effect of early onset criminalization of especially Black and Latinx youth. Officers often targeted Black children, as shown in the complaint data. Officers tormented and assaulted schoolchildren as young as 11. There was continuous and blatant abuse of power. Community policing perpetuated a carceral culture. The only known response to crime was to bring in more police. As such, when there were localized incidents, citizens often requested a ministation or increased police presence.

Rise of Vigilante Justice

Community policing is not necessarily the initial provocation for vigilante justice, but it has played a role in emboldening vigilantes. It creates a dangerous environment of alleged award or encouragment associated with citizens taking “crime-fighting” into their own hands. The environment was particularly dangerous considering the heavily-armed nature of the American public. Racism, and the subsequent racialized conception of the criminal created targets out of young Black men. The rise of racist vigilantes continued long after Mayor Coleman Young. Dr. Angela Davis used the vigilante model to describe contemporary murderers like George Zimmerman who killed Trayvon Martin in 2012, and even more recently, Travis and Gregory McMichael who shot and killed Ahmaud Arbery in February of 2020. Any administrative encouragement of civilians to engage in policing of any kind is incredibly irresponsible, especially considering the rate in which the trained officers shoot and kill people.

However, as historian Edward Littlejohn points out, community policing is not the origin of encouraging vigilantism. He traces it back to 9th century English common law called “posse comitatus” which is “power of the country” in Latin. The law meant that “all citizens were expected to pursue a felon and use their best efforts to capture him.” The idea of engaging the public in fighting crime is not new. That said, in that age, the public did not have access to heavy artillery and the chief concern was retrieving stolen property.

Vigiliantism has been further glorified in American media. Historian John Wesley Domm coined the “John Wayne myth” to describe the phenomena of civilians’ imagined heroism for their acts of vigilante justice. John Wayne, among other popular film heroes were “ordinary men” that ignored civil laws to fight crime. In film these men were celebrated for keeping their communities safe, and being there when the officers could not. Hollywood reinforced the idea that those who may engage in petty theft are inherently criminal, evil, and deserving of punishment. Very often, the white vigilante hero would end up shooting and occasionally killing the on screen criminal, only normalizing the idea of justified gun violence. Just as the popular Western films dehumanized Indigenous people, they simultaneously heroized the white vigilante. Thus while the media contributed to the romanticization of the vigilante identity, community policing efforts and administrative encouragement provided the vigilante with government permission to act on their violent fantasies. Likely, they believed to be immune from legal consequence. Sometimes they were, like in the case of Andrew Chinarian who shared a camaraderie with officers and was able to maintain his business despite shooting and killing Obie Wynn. The media and the national push for community policing played a role in conditioning the public to breed and excuse vigilantes. Along the same vein, in “Are Prisons Obsolete?” Dr. Angela Davis discusses how the omnipresence of police and prisons in our media has normalized the carceral system. It hinders us as a collective from imagining a world without such reactions to perceived crime. Vigilantism did not originate in the 70s or with Coleman Young, but we cannot ignore the role of community policing programs and policies, particularly in conjunction with popular media in the rise of violent vigilante justice.

Police Violence Behind Closed Doors

Andrew Chinarian and Obie Wynn were two key figures in the Livernois 5 incident, which did not reach the level of national coverage of the 1967 outbreak, and it is often cited in the papers as a “near-miss” from a repeated catastrophe. This was the first major test for the efficacy of Young’s affirmative action policies and the supposed improved community-police relations. Mayor Young cites the outcome of Livernois 5 as a victory for his reforms and his approach as mayor. He is accredited with playing a pivotal role in maintaining relative peace during the incident. As noted by historian Michael Stauch, this celebration obscures the violence done by the DPD behind the scenes, which came out in the case. To celebrate this as a win for the reforms is to act as if the reforming is complete. While the violence of those three days did not escalate to that of 1967, in the year that followed, the DPD continued to coerce witnesses, abuse the convicted and exemplify the same racism. Ignoring this violence serves a grave injustice to the Black community that rallied so diligently for Young’s victory and for his promised reform. Mayor Young is not responsible for the actions of the department or the state’s criminal justice apparatus, but his celebration lacks vital nuance.

The police and community may have worked together to some extent in reducing the violence in the public eye during those three days but behind the scenes, largely hidden from the public perception, immense violence remained. Raymond Peoples, one of the Livernois 5, wrote a letter while in jail denouncing Young, claiming that he is “all bark and no bite when it comes to seeing justice.” This is a sentiment shared by the left: frustrated that a once progressive activist has settled for moderate reform. It should be noted that shortly after his acquittal, Raymond Peoples went on to found Young Boys Incorporated, a gang that was structured to use juveniles to sell drugs. [For more on Peoples and YBI, click here]

Young’s success is defined by the containment of the violence — it did not spread to other neighborhoods. The violence was contained. In those three days, the incident remained in the Livernois-Fenkell community and in the year that followed, all violence was inflicted by the police, the prosecutor, and Judge Gillis. Violence was reserved for the jail cell and the courtroom.

The media portrayal of celebrating officers mirrors the coverage of the 1967 rebellion. The only difference is the inclusion of the role of the community in reducing the violence. We believe this reflects the emphasis on community policing in Mayor Young’s platform. Thus the community is being celebrated as an added police force — not for community sake but rather as an extension of the DPD. The media encourages the community to be “tough on crime” while effectively criminalizing the fight for justice. The protesters were excluded from “the community” and the protests were framed as a melee in the papers. Journalists blamed the protesters for the disturbance and the consequent mass arrests instead of holding the department responsible for a radicalized panic that culminated in tear gas. Those that fought for justice were shunned while those that chose silence were celebrated.

The attempt to celebrate the community and Mayor Young is in part a reluctance to give up on the idealized vision that Young represents. That is, a Black man leading a black majority population and doing it successfully. This is particularly true for the upwardly mobile Black Detroiters. Young’s mayoral position serves as a culmination of a long battle for civil rights and administrative representation that marked the decades prior. Therefore, “taking to the streets'' was deemed no longer necessary. The Livernois 5 had less support and it was largely a class issue. The image of equality and peace was enough for most upper-middle class black communities while the working and lower class communities continued to suffer and saw little of Mayor Young’s promised improvements.

The emphasis on community and any attempt to silence the injustice done during the trial is also very likely an issue of public image. Violence does not bode well for Detroit’s already fragile national reputation. According to the archives, Mayor Young was frequently concerned with the media representation of Detroit and the reputation that incidents perpetuate. The papers worked to exclude protestors from the otherwise “peace-seeking” community. “Peace” in this case was understood as passivity and it is a powerful and positive buzzword to spur tourism. In Coleman Young’s platform of “Law and Order with Justice” the pursuit of justice was forsaken in favor of creating a docile or “peaceful” constituency.

Works Cited for this page:

Citizens Complaints to Detroit Police Department 1974, Boxes 33-35, Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Davis, Angela Y. Are prisons obsolete?. Seven Stories Press, 2011.

Domm, John Wesley, “Police Performance in the Use of Deadly Force: An Analysis and a Program to Change Decision Premises in the Detroit Police Department”. Doctoral Dissertation, Wayne State University (1981)

Obie Wynn Killing Media Coverage 1975-76, Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Folder 25, Box 17, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Edward Littlejohn; Geneva Smitherman; Alida Quick, "Deadly Force and Its Effects on Police-Community Relations," Howard Law Journal 27, no. 4 (1984): 1131-1184