The Juvenile Justice System

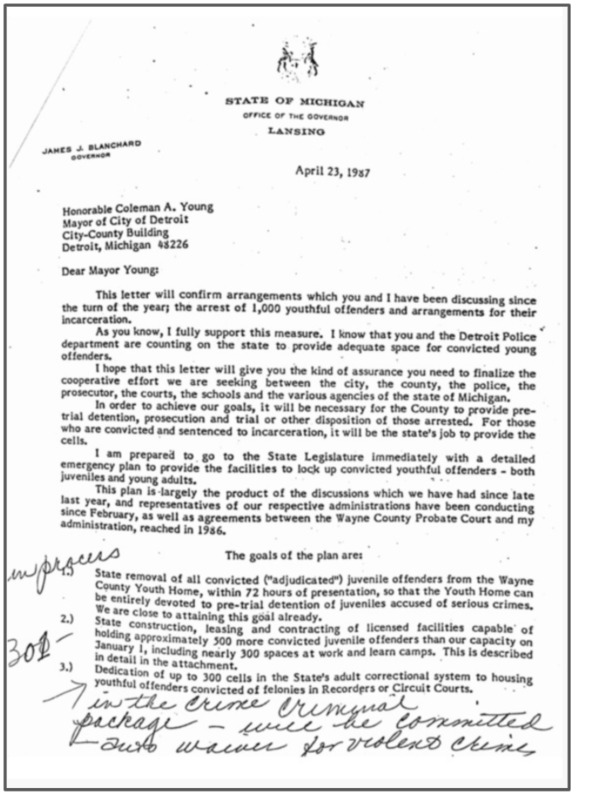

In 1985, the Michigan legislature began an agressive counteraction against juvenile criminal offenders. The hysteria surrounding juvenile violence between 1982 and 1985 caused the state and local governments to react in a way that changed the goal of the juvenile justice system from rehabilitative to punitive. By 1986, Police Chief William Hart wrote to Coleman Young asking to “revitalize the gang squad to it’s mid-1970’s level" used when youth gang violence was at its peak. As a result, increasing numbers of legislators from both sides of the aisle introduced bills that would institute “automatic waivers,” which would transfer juveniles normally under the juvenile court’s jurisdiction to adult criminal court if they were charged with committing violent crimes. The movement was led by Representative Michael Bennane, a Democrat representing part of Detroit, who joined with then chief assistant prosecutor for Wayne County Elliott Hall to pass a law instituting automatic waivers for any violent offender over the age of 15.

Although early attempts were unsuccessful, in 1988, the legislature successfully amended the juvenile code to allow prosecutors to decide which juveniles could be prosecuted as adults. As recently as 1996, the Michigan legislature lowered the age for juveniles eligible to be tried as adults to 14 years old. Before 1985, juveniles were rarely punished in the same manner as adults, following an American jurisprudential tradition of rehabilitation that originated in the early 19th century; however, the events of 1982-1985 created a juvenile justice system more focused on providing punishment than before. Whereas before juvenile criminal behavior was treated after they had committed a crime, the City of Detroit and State of Michigan created measures to prevent juvenile delinquency on an unsubstantiated assumption that juveniles were more likely to commit crimes than adults.

The Beginning of a Juvenile Justice Revolution

Juvenile corrections began as a rehabilitative practice designed to help juveniles move on; however, this “rehabilitation” was imperfect in practice. The “Houses of Refuge” were designed to provide housing, teaching, and general rehabilitation for delinquent youth in order to separate them from troubled home environments or the perils of adult prison. In reality, these homes were abusive and oppressive, and children were subject to forcible institution by the doctrine of parens patriae, by which the state was allowed to take custody over delinquent youth in almost any circumstance. It was not until 1967 in the landmark Supreme Court case In re Gault that juveniles tried in delinquency proceedings were given the right to due process. Although a necessary step in civil rights, due process granted the state with new tools to prosecute youth as criminals, and consequently, in adult criminal court. Research into the period between 1982 and 1985 calls into question why the government reacted so significantly to youth crime throughout this time.

An Era of Youth Violence

Beginning in 1982, a combination of observed trends in youth violence occurred simultaneously. This created a dangerous notion amongst the media and the public that juveniles were the largest source of crime in Detroit. One of these was the fear of groups of violent, delinquent youth. After the fall of Young Boys, Incorporated, a power vacuum ensued in which no single entity controlled the narcotics trafficking market in Detroit. Instead, a number of disorganized youth gangs encroached on the sale of crack. Although they were not nearly operating on the scale of Young Boys, Incorporated, the public and the media became anxious about an apparent resurgence of gang violence. A contemporary Detroit Free Press reporter described the public as having “the notion of these young super-predators… that if they had been able to form a stable gang structure that there would be an evolutionary climb [to become a more organized gang."

The apparent rise in impromptu gangs occurred against the backdrop of youth-on-youth violence taking place not in the streets, but in schools. Several high-profile cases of youth being shot during school hours caught the public eye. In the case of Marco Hardaway, a 16-year old student who was shot at school in 1983, he was accused by the media as being shot as a result of a gang dispute. His mother and brother disputed the claim that he was ever in a gang, but a dangerous connection was drawn between juvenile violence and gang affiliation. In kind, the police department resorted to anti-gang methods to combat juvenile violence. The Youth Crimes unit employed tactical operations utilizing plainclothes officers, surveillance methods, and the use of hand-held metal detectors used to “sweep groups found loitering.” Additionally, the Detroit Police Department started a “Sweep Operation” in schools, in which they would raid students’ lockers at random in search of weapons and illicit materials.

As part of the broader criminalization youth and the perceived problem of youth crime, the Coleman Young administration instituted a curfew on October 30, 1984, also known as “Devil’s Night.” Devil’s Night is still a tradition in Michigan today, but the holiday in the years preceding 1984 saw thousands of fires started in the multitude of abandoned houses across the city. The consequent clamor for harsher measures resulted in the city instituting a curfew for all minors on Devil’s Night, a law that is still in effect today. The curfew was met with support from community, and Mayor Young instituted curfews during the summers of 1984 and 1985.

Spotlight: Marco Hardaway

Hardaway was a 16 year-old student at Henry Ford High School off of Eight Mile Road in Detroit. Marco was shot and killed during school hours on September 13th, 1983. His brother Terrence witnessed the event, saying that Marco attempted to break up a fight between other youths involving a gun, and once he grabbed the gun-wielder's arm he was shot to death. Media coverage of the event inferred that Marco had gang affiliations, with one newspapers claiming that he may have been a member of either Pony Down, Puma, or Gucci gangs; essentially, all of the gangs at the time. While the police believed Marco to be affiliated with a gang, Marco's mother and brother adamantly disputed that charge. "I don't know why they keep bringing that up," said his brother Terrence, a senior at Henry Ford High. "He wasn't in a gang-you can ask anybody. Marco wasn't like that." Marco Hardaway represents not only the tragic loss of a young person to violence, but a biased misrepresentation of youth as being connected to a larger problem; namely, that each young person involved in a shooting must be affiliated with a gang. Shootings such as this started a movement among students and other members of the public to question why youth had access to so many firearms. Organizations like the Marygrove College Task Force published that 365 children were shot in 1986, and advocated for Councilwoman Maryann Mahaffey’s ban on handguns. Marco Hardaway's death galvanized a new wave of policing aimed against youth in schools.

Mayor Young's Controvertial Crime Moves

Coleman Young's anti-crime project was widespread across the city and reported about extensively in local newspapers and magazines. The project was the Mayor's response to an increase in overall crime throughout the late 1970s and early 80s. The program was geared toward an increase in community involvement in decreasing crime and community policing. The policies, misunderstood by many, harshly and repeatedly targeted black communities of Detroit.

Sources:

James Blanchard to Coleman Young. Folder 1, Box 15. James Blanchard Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. April 1987.

Young Anti-Crime Cartoon, illustration. Box 179, Folder 2, Coleman A. Young Papers. Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection.

Wilson, Danton. Michigan Chronicle. "Slain Teen's Kin Reject Gang Fight Theory." September 1983.