V. Repercussions (1990-93)

Note: section 5 is still in development and should not be cited or quoted or reproduced without contacting mlassite@umich.edu first. The data on police homicides in this section is also incomplete.

“I believe that 99.99% of our officers are good, hard-working officers and would not coast. Officers are sworn to protect our citizens and our property and any person in a leadership position that asks officers to coast and risk the health and welfare of our citizens, in my opinion, should be locked in a padded room. Any officer, whether he or she be an investigator, a sergeant, a lieutenant, inspector, commander, or deputy chief will be put in the fast lane on his way out of this department.” -Police Chief Stanley Knox at the Board of Police Commissioners on September 30th, 1993

Detroit in the 1990s

The Detroit Police Department in the early 1990s was commanded by Chief William Hart until his conviction for embezzling funds in 1991, when Chief Stanley Knox took over the department. In the above statement from 1993, Knox describes “coasting” as ignoring when another officer has acted inappropriately, whether it be violently or through another form of misconduct. “Coasting” was a trend within the department throughout Coleman Young’s term as mayor. From the beginning of his term, his goal was to reform the police department both in terms of stopping crime and ending police brutality. Those he appointed as Chief of Police were faced with the same challenge. Hart failed to reform the department; and he himself did not exemplify his intended reforms as he was convicted of embezzling money from the police department in 1991. Knox fronted a “tough reformist” approach, but the rate of police brutality under him did not subside.

Coleman Young’s mayoral career came to an end with the election of Dennis Archer in 1993, but when he entered his 16th year in 1990, Detroit did not look how he had pictured it in 1974. His legacy was being debated among citizens of Detroit and its suburbs. Debates circled around whether or not he was a “reverse racist” and whether he was responsible for the damage he had done to the city. White citizens of Detroit blamed Young for the deteriorating condition of the city although there were many other factors that contributed to Detroit’s plight in 1993. “White flight” had reached an all-time high, and the New York Times published an article called “The Tragedy of Detroit.” This type of media attention was common and focused on Young’s failure to realize his economic goals and the racial tension the city had not shaken. Race took the spotlight in all aspects of the city’s management and day-to-day activities, even after years of Young attempting to reconcile the racial divide.

Racial tensions manifested themselves in the interactions between police and citizens, which exhibited violence at an alarming rate. However, race was not a highly publicized factor in media attention to police violence in the early 90s until the death of Malice Green. As the most publicized case of a black man killed by white officers during this time period, the Malice Green case changed the way that ordinary people thought about justice. Reports within the police department did not always include the race of the citizen or the officer(s), and there were multiple instances of African American officers committing acts of violence and being charged with crimes. However, trends of police misconduct indicate that most violent acts were committed against young, African American males, similarly to the previous twenty years under Young. The 90s also marked a period of increased reporting on instances of police violence against other minority groups like the Latinx community in Southwest Detroit and the LGBTQ+ community.

By the end of 1993, the city faced a turning point similar to the one it faced in 1973 when Young was elected. Detroit could continue in its financial turmoil or bring about reforms under Archer that could change the dynamics of the city. After the exposure of systematic corruption in the DPD, Archer appointed Ike McKinnon as police chief once again in an effort to reform the police department. Locally and nationally, people wondered if Detroit would ever be able to sustain itself economically with a population that was continuing to flee to the suburbs and a reported crime rate that was above the national average. Although crime had decreased, it was still a major focus in cities throughout the United States, and especially in Detroit.

National Trends

National crime rates reached their peak in 1991, especially violent crime rates, prompting a resurgence in police crackdown. The media reported cases of police violence in spurts, with a few events being covered nationally for weeks or years while others went unreported altogether. However, excessive force by the police caused backlash in certain cases as seen with the beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles in 1991 and the riots that ensued in response to the involved police officers’ acquittal. These riots garnered media attention in Detroit, and brought special attention to the brutal murder of Malice Green at the hands of seven police officers a few months later. Many citizens were shocked that an event of that nature could occur in Detroit, but trends of police violence throughout the country highlight that it was not the only city with problems regarding bad police community relations.

George H.W. Bush, President from 1989 until 1993, continued in the direction of Ronald Reagan, promoting a punitive law-and-order platform. The national War on Drugs continued to manifest itself in Detroit through federal laws. Policing in Detroit in the 1990s was fundamentally shaped by the massive drug and gang crackdowns that were accelerated by the 1986 and 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Acts. Overpolicing was a common result of police abusing their power in alleged attempts to crack down on gangs and drugs. Criminal reform in Detroit had failed under Young, but was being shaped in other cities simultaneously. Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley of fought for a tough-on-crime attitude coupled with appropriate punishments for officers who had broken the law. In Detroit, however, the expanded reign of the police was not paired with proper oversight, which resulted in an excessive amount of officers never being charged for instances of violence.

Democrat Bill Clinton was elected in 1992, and in 1994, he signed into law the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act that allocated a larger budget to hire more police officers around the nation. This federal bill was controversial, and still is today, as it was seen to target communities of color and provide police forces with a larger budget to do so. In the wake of the height of the War on Drugs and Crime, proponents were able to garner bipartisan support at a time when public opinion strongly supported a tougher war on crime. Its proponents claim that it was the reason for the declining crime rate of the 90s, while adversaries claim that the bill sparked mass incarceration and had no effect on the falling rate. Despite claims about the national crime rate, Detroit was still viewed as one of the most dangerous cities in the country. This proved to be especially true for civilians suffering from police violence, which was revealed in an exposé in 2000 detailing the rates of police violence during the 1990s. The rate had not decreased since the height of the War on Crime and Drugs. This expose is what led to a 2003 Federal Consent Decree in which the Detroit Police Department was required to have oversight from federal officials.

Police Violence/Misconduct and Archival Silences

The primary sources included in this section of the website are mainly from archival research in the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University, the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, and the Burton Historical Collection at the Detroit Public Library. The archives provided us with a tremendous amount of information about policing in the early 1990s, but we know that they did not give us a complete picture of what was happening in Detroit. We reasonably suspect that there are holes in the information we discovered based on the leads we could not find any follow-ups for and the information we know should be there, but isn’t. By their nature, archives are not unbiased sources of information. The papers that public figures chose to keep and give to archives represent their perspective of what was important to them at the time.

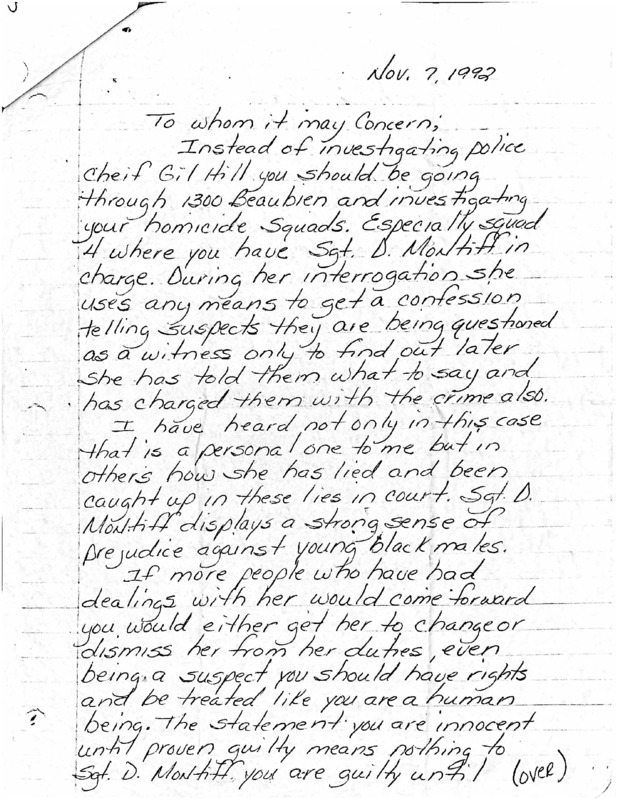

These archival silences are both deliberate and indeliberate because of the nature of conducting this type of research. It may be that the location of particular pieces of information are unknown or that documents have been discarded over the years. In the case of deliberate silences, they are likely due to the politics of police violence in the early 90s. Police violence is and was a trend that began before the time period covered in this exhibit. Citizens of Detroit were fed up with the lack of action on the part of the government in punishing officers to the fullest extent. As one citizen described, “Once again we’re talking about another form of police brutality.” This information was found in the archives in Mayor Coleman Young’s papers, which included other letters from citizens regarding police violence, but it is probable that not all citizens sent their letters to Young. Within the Detroit Police Department, there had been a longstanding tendency to misreport and underreport instances of police violence. Many shootings reported during this time period were considered justified after an internal review, and any time at which an officer feared for his or her life, shooting a civilian was considered justified. This could be one reason that civilians did not report shootings: they knew that the officer would not be held responsible.

Police homicides that were reported in The Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News reveal important truths about police brutality, but the few that were covered served as sensationalist stories to increase readership in newspapers. Reporters and editors of the newspapers chose to only feature large-scale incidents that had implications beyond reporting on police violence. For instance, Malice Green garnered media attention because of the public’s response to his death and the racial dynamics of the incident [move this down]. Homicides like these were placed on the front page and covered by the media for months or even years, following community reactions and the trials of officers. Further, what was reported about police homicides usually came directly from the police department, except when major events like the death of Malice Green occured, which prompted further media investigation. Reporters had depended on police relationships with officers and it is doubtful that they probed officers for information that did not reflect the police’s point of view. If they were to report on the police in an unfavorable way or represent multiple viewpoints of a police homicide, journalists could have lost an important and trusted source in the police.

Many police homicides that we discovered were simply from a letter to the mayor or from the Secretary’s report during the Board of Police Commissioner Minutes. This suggests that there are many more instances of civilians killed by police that we have not identified. The gap in our research is irreconcilable as a result of the lack of records kept or disclosed by the DPD. There is no official record stating how many civilians were killed by Detroit police officers, but an expose written in 2000 claims that there were an average of 10 police homicides per year from 1990 to 1998. We have not identified nearly this many, but we hope that our exhibit can bring awareness the murdered civilians that we have identified.

Sources used for this page:

The Detroit Free Press

The Detroit News

The New York Times

Christopher Agee, “Crisis and Redemption: The History of American Police Reform since World War II,” Journal of Urban History (2017), 1-10

Max Felker-Kantor, “Liberal Law-and-Order: The Politics of Police Reform in Los Angeles,” Journal of Urban History (2017), 1-25

Coleman Young Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

NAACP Papers, Box 90, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.