Police/Community Relations

“I have tried to be a patient man knowing that things would work out for those who are honest and just. But this does not seem to be the case on the Detroit Police Department.” -Sergeant Walter L. Robinson, April 18, 1993

Young’s Term

This time period covers Coleman Young’s last four years as mayor of Detroit. His focus on the Police Department and fighting crime left a lasting impact. The nature of this impact was debated among citizens and other public officials. The defining police incident of the last part of Young’s tenure was the beating death of Malice Green at the hands of seven police officers. This incident brought to light the changes that Young had made within the Detroit Police Department and the promises that he failed to keep. In an article in the Detroit News, the columnist Bill Johnson points out that Young was elected during the time of S.T.R.E.S.S. (link to DUF) and his platform was largely dependent on integrating the police racially. Johnson claims that Young was at fault for the many police homicides and brutality incidents during his career because of the police were treated with blatant favoritism . Police Chief Stanley Knox was chosen by Young and propagated a rhetoric of officers not being at fault for harming civilians. The Board of Police Commissioners that Young had created included members that had been convicted of fraudulent activities.

The skepticism surrounding some of Young’s reforms became clear in the aftermath of Green’s death.

Others offered resounding praise for the changes Young implemented within the police department. Betsy DeRamos, in an article in the Detroit News, stated that “Detroit has come a long way for sure since the 1960s when police officers roamed black neighborhoods which they called ‘zoos’ looking for ‘monkeys’ to whip.” The data on police violence suggests otherwise, as it occurred in primarily African American neighborhoods in most instances. Later in the article, she states that “We have certainly come a far distance from the days when a few, hate-twisted officers in the police decoy unit known as STRESS acted as though their badges gave them a license to kill young black people.” Once again, this statement is inaccurate based on newspaper and archival findings about police homicides. More police homicides from 1990-1993 were of young black men than of any other race/gender combination.

Young’s own conception of the Detroit Police Department mirrors that of DeRamos. During remarks at the Board of Police Commissioners in 1992, Young stated that he believed his police department to be “the best, most progressive police department in the nation.” He even went as far to say that the police department was “a part of the community it serve[d], rather than a form of occupying army.” This characterization of the police department was more of an ideal outlook than a truthful one, and it was based on the reforms that Young had hoped to perform successfully. Three of the focal points Young mentioned at the beginning of his mayoral career are mentioned below.

Affirmative Action

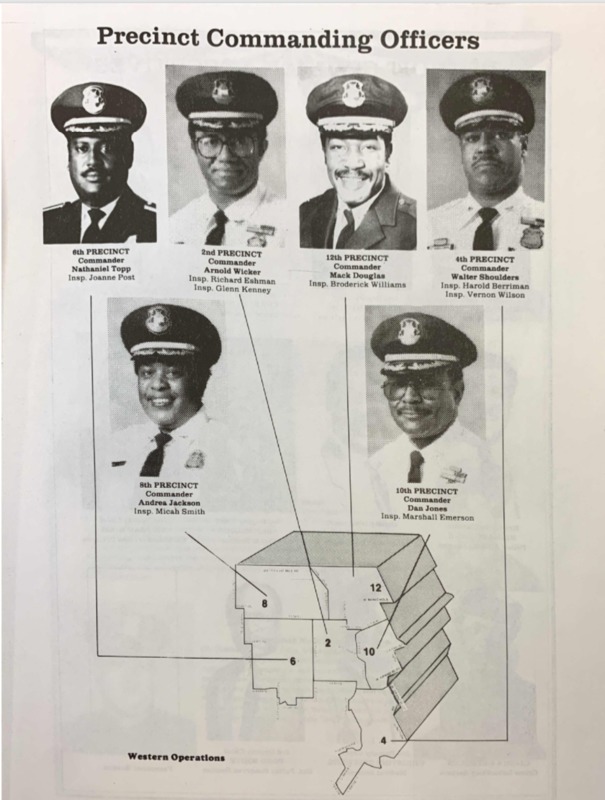

Young promised two things regarding the composition of the Detroit Police Department: a racially diverse force and more women on the force. In 1990, 20% of the police force was female, and females had only been allowed to police the precincts starting in 1975. Although there were more women on the force by this time, they complained of having to prove themselves more than men did because of the gender imbalance in the department both among their peers and among citizens, who did not respect their authority. Women in high positions in the department were rare, and some claimed that they received more pushback for their sex than they did for their race if they were African American. Mary Jarrett-Jackson, the first female commander, appointed in 1986, served as a role model for other women on the force and garnered respect for female officers.

Racial composition of the force was a more publicized goal and it received much media attention. Young’s intention at the beginning of his term was to make the police department reflect the racial composition of the city, which was experiencing “white flight” and had an increasing African American population. In response to a lawsuit filed in the ‘80s against the City of Detroit, Coleman Young stated that “the polarization between the police and the black community gradually gave way to a spirit of co-operation.” In his memoir, he stated that “Despite staunch and collective resistance, my administration never gave up on affirmative action, and the reward was in the relative climate of harmony that prevailed between the police and the citizens of Detroit.”

This optimistic picture of affirmative action is challenged by instances of police officers using violence in black neighborhoods (link to patterns of police misconduct) in far greater numbers than in white neighborhoods. We have also uncovered complaints from within the DPD about both racism and favoritism. In April of 1993, Sergeant Walter L. Robinson of the 11th precinct wrote a letter to Mayor Young expressing his concerns about racism within the department. He claimed that he had been continuously discriminated against and had filed complaints, but no action had been taken. Instances like these were likely common throughout the DPD despite efforts to eradicate racism in the department. Officers also claimed that there was an unfair system of favoritism that controlled promotions and hirings. Jerald Washington, a police officer and attorney, was seventh out of 400 people on a list for promotions and scored the highest on the test out of all African Americans. However, he was not chosen for a promotion. Young chose seventeen men and women to be promoted, and there did not seem to be any pattern. They had no notable characteristics besides their close political ties to Young and his colleagues. The promotions were not a result of affirmative action mandates, but rather Young’s personal preferences. The author of the Detroit Free Press article detailing this process, Susan Watson, acknowledged that the DPD had the highest percentage of women and African Americans on the force of any major police department, but she found this statistic worthless when she discovered that “Mayor Coleman Young threw the eligibility list to the wind and handpicked the winners.” Washington was a part of the trial board who conducted hearings for officers that had been accused of misconduct, which could present an explanation for why he was overlooked. HIs willingness to discipline other officers may have put him at a disadvantage for a promotion for fear that he would expose the rampant misconduct within the DPD.

However, those who praised the effects of affirmative action did cite improved community/police relations on the basis of race. After Anthony Riggs, an African American citizen of Detroit, was allegedly murdered by his brother-in-law, the Interfaith Council of Religious and Civic Leaders expressed gratitude for affirmative action, giving it credit for the rapid and proper handling of the case. He stated in an announcement at the Board of Police Commissioners that the “fruits of [affirmative action] are now ripe for all to enjoy.” The City of Detroit’s response to a lawsuit alleging the failure of affirmative action states that “It is, quite literally, indisputable that these policies have broadly contributed to an improvement in police-community relations.” This information is explicitly biased, as it is coming from the defendant in a lawsuit, but it also reflects the sentiments of many citizens who lauded Young’s efforts and saw a noticeable difference in the composition of the police force. Some, however, criticized the policy as not doing enough, as the composition of the force still did not fully mirror the composition of Detroit. The success of affirmative action in terms of diversifying the police force is irrefutable, but questions remained regarding the extent of its effect on the frequency of police violence and misconduct.

Community Policing

Another of Young’s primary goals for the DPD was to involve officers in closer community/police relations. He took swift action to accomplish this at the beginning of his term, implementing programs like mini-stations (link to Team 1), but the 1980s brought a reversal in policy. Militarized policing (link to Team 4) and drug raids were common, and police were less an integrated part of the community than a predominantly militant department. In the 1990s, Detroit citizens once again realized the need for community policing to improve the standing of the DPD in the eyes of citizens. An article written in the Detroit News emphasized the previous success of police mini-stations , and commander Dorothy Knox advocated for their continued use at all 54 locations. The significance of building relationships between community members and police officers was used as a method of reducing crime, but it dramatically increased police presence in neighborhoods, especially low-income African American neighborhoods. The widespread praise of mini-stations is partially misdirected. Although they may have reduced instances of citizens committing crimes against other citizens, the increased police involvement in these neighborhoods may have led to more instances of violence along with increased arrests among black and Latino youth. This pattern is likely the same with other measures taken to enhance community policing.

In the 90s, police mini-stations received praise from many members of the community, especially white residents. There was little backlash during this time period about the increased presence of police in local neighborhoods. A questionnaire was delivered to Detroit citizens and some were interviewed and their responses were overwhelmingly positive. People stated that mini-stations helped to reduce crime and bettered relations with police. During a Board of Police Commissioners meeting in 1991, citizens were worried about losing officers at mini-stations and voiced this to the DPD. This concern stemmed from the budget cuts that the DPD was facing, which resulted in less officers being available at mini-stations. However, the comment we discovered was from the president of the Brightmoor Concerned Citizens. Brightmoor, one of the only predominantly white neighborhoods left in Detroit in the 90s, was and is a primarily white neighborhood located on the outskirts of Detroit, so the request for the presence of officers in that neighborhood was likely to “protect” them from people from outside of their community. We found no requests for increased police presence and mini-stations from people in low-income, African American neighborhoods.

Reactions to police occupancy of neighborhoods varied, but it was primarily people concerned about their safety that expressed concern about a lack of officers. Some citizens trusted police and requested their protection, such as two shop owners in the 4th precinct that worried about gang presence in and around their shop. They feared for their safety, but were afraid to take action without assistance from police. The couple pleaded for Chief Knox to stop laying off officers and continue to hire more so that their business would be protected. Another man complained that his grandson had been missing for two months and the police had done nothing to try to locate him. This man lived in a primarily African American and low-income neighborhood. Comparing these two complaints about lack of police presence indicates an important pattern. In Southwest (link to Bernie’s page), where the 4th Precinct is located, and at the address of Earvin Davis, Sr., whose grandson was missing, police were not carrying out their duties to protect citizens to the fullest extent. Instead, they were likely more concerned with other petty crimes, like traffic stops, that resulted in excessive use of force on behalf of police.

Sources used for this page:

Coleman Young Papers, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Detroit News

The Detroit Free Press

Julio Perraza Collection

Detroit Police Department Annual Report 1990