Policing In Schools

A powerful manifestation of racially prejudiced discretionary policing is seen in the examination of the way students are criminalized from a young age in public schools. Schools exist in a bizarre jurisdictional gray area because of the complex way that student conduct is governed both by internal disciplinary guidelines and procedures and simultaneously by local, state, and federal law. The inner workings of this perplexing system become even more murky in instances when School Districts decide to allow police into their schools—as the DPSCD did in 1975 when its board voted to allow armed police officers past the schoolhouse gates.

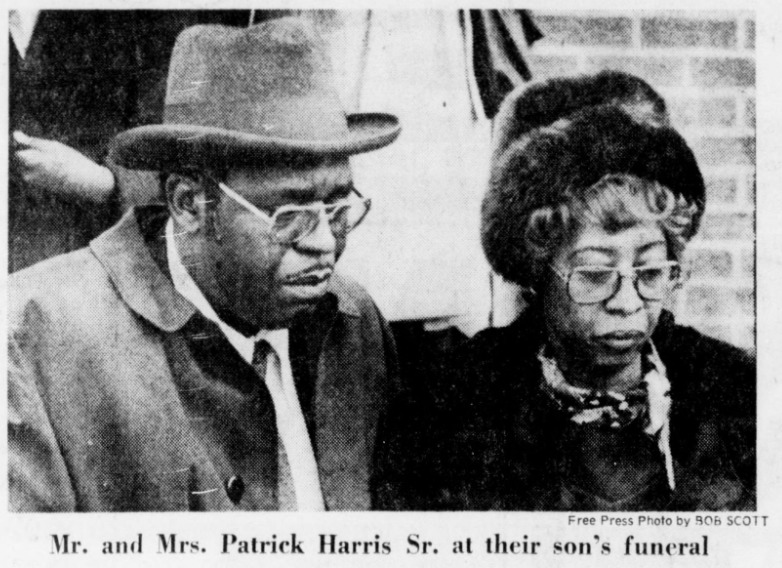

The Board of Education's decision to put armed police officers in schools certainly faced criticism at the time, but by and large, the complaints were drowned out by a much larger coalition of supporters. It's telling that the Michigan Chronicle—an African-American newspaper—would run an alarmist cover story about violence in the schools that called for a harsh response from the city's criminal justice apparatus. That January 1975 cover story typified widespread sentiment building among parents, teachers, and administrators for months that something drastic needed to be done to quell the violence.

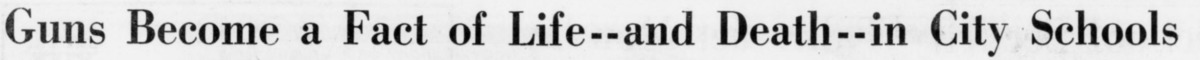

The moral panic about the prevalence of violence in schools was not limited to the black newspapers whose readership was most directly affected by the instability. Newspapers with larger and whiter audiences that extended throughout the city and into the suburbs like the Detroit Free Press were all over the issue of violence in schools. The sheer universality of the outrage about the problem with school violence suggests that these were not a few isolated incidents sensationalized by the media to sell newspapers. This was a genuine city wide emergency. The anger and desire for a solution was plaguing the minds of government officials across the city. People were in danger and something needed to be done. But the uproar was not just an abstract call for action, it was pretty unanimously in favor of an aggressive, punitive crackdown.

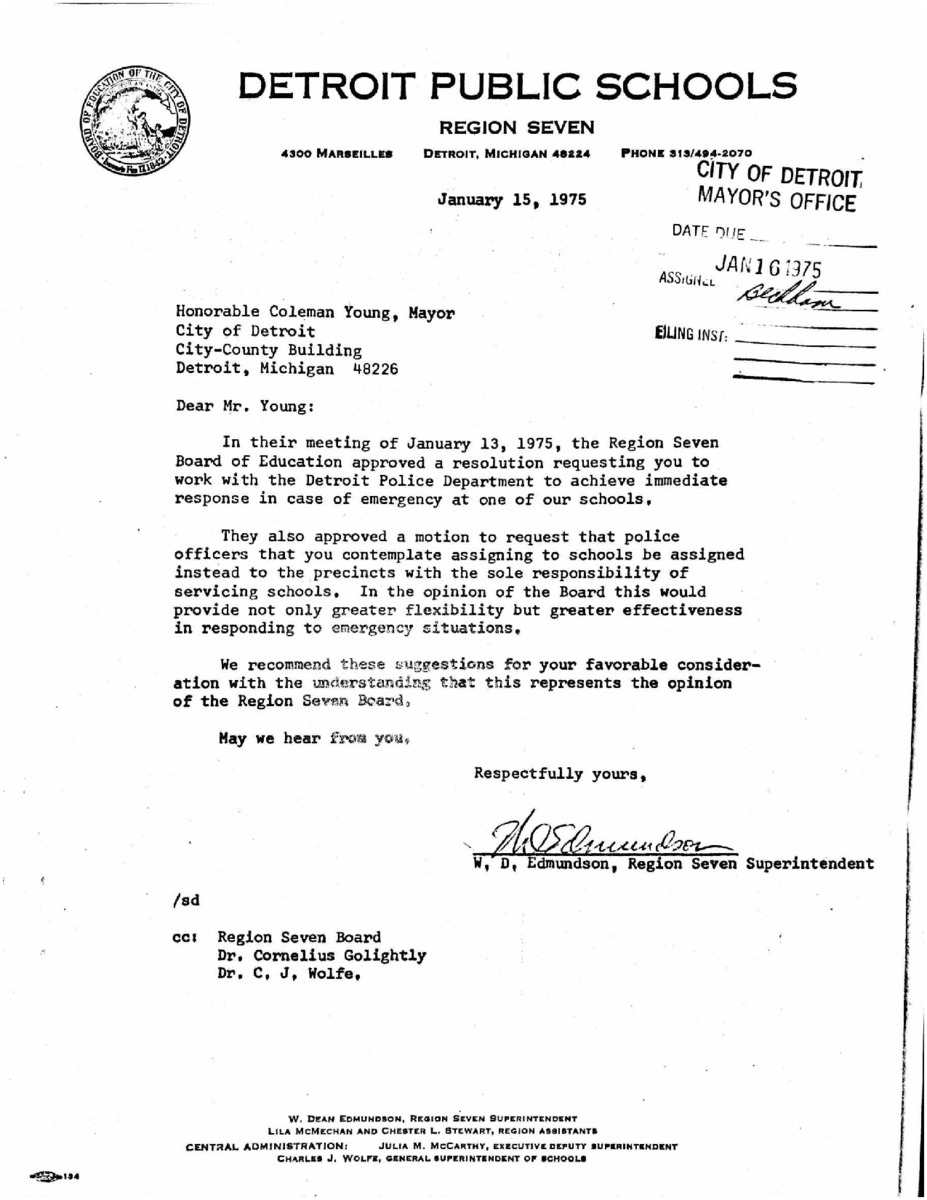

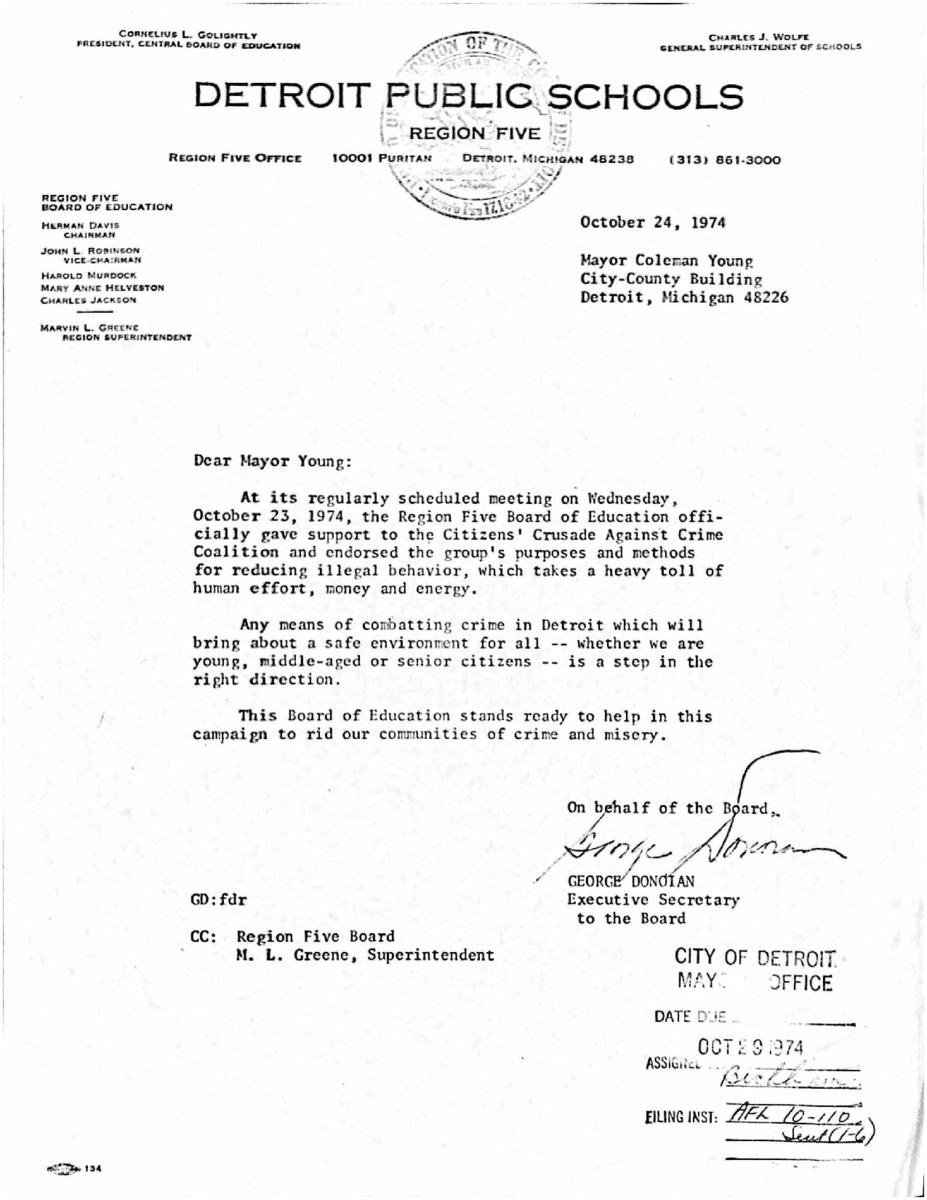

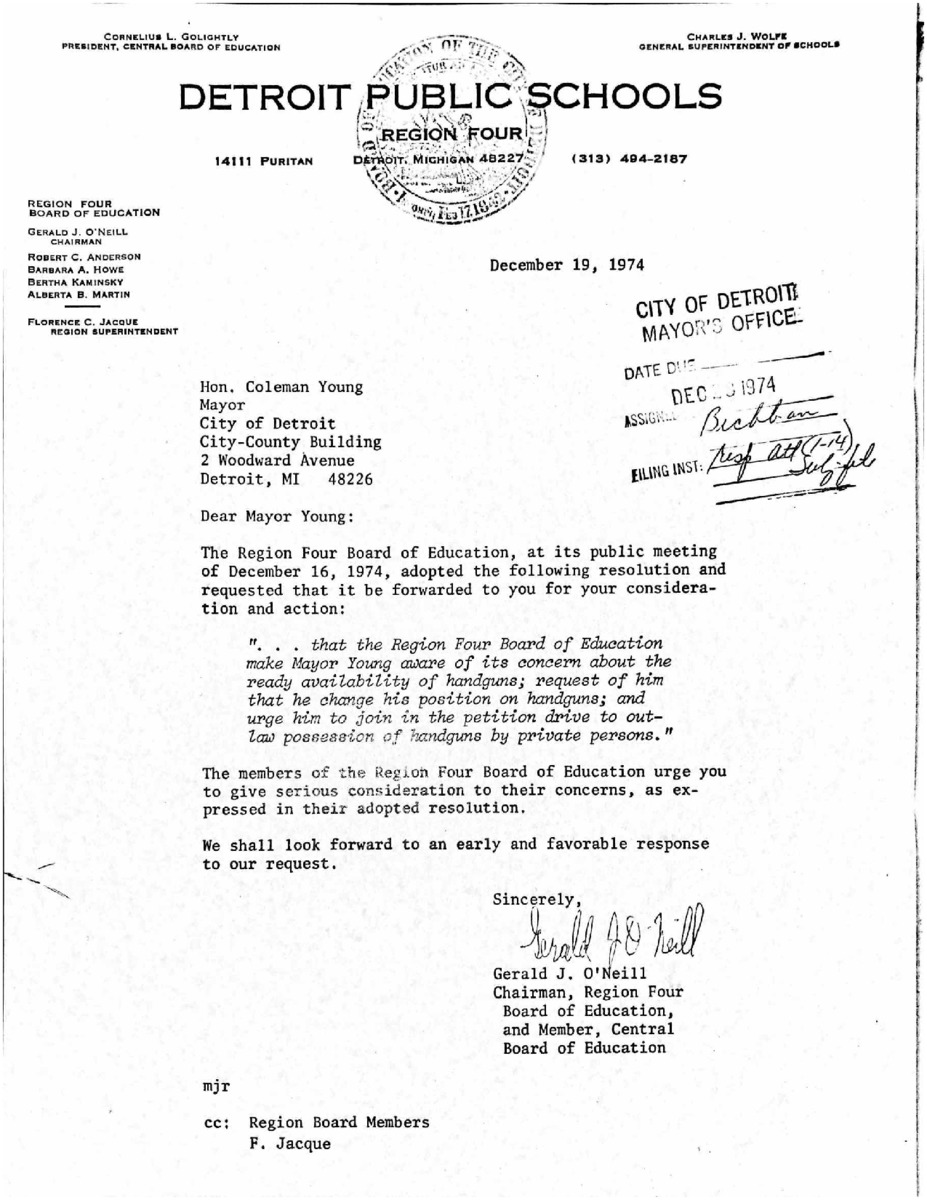

In Detroit there is not a single school board that governs over the entire district. The power is instead divided among many regional boards so they can best address the individual concerns and needs of their communities. This policy was widely popular in black and white communities and across class divides. Letters from board members saved in Mayor Young's papers show that their was support for armed officers in schools from many different regional boards that each represented schools with varying demographic breakdowns. There was no record of any regional boards expressing concern with the policy in the months leading up to and following the inception of the program when the policy was being hotly discussed by city officials across many departments.

To understand the way that the deployment of police in schools disproportionately targeted locales with black students it is crucial to be cognizant of the rapidly changing racial demographics in the city at large and the public schools more specifically. In the years following the 1967 uprising of black Detroiters—who rose up with righteous indignation after enduring years of brutal systemic racism by way of police brutality and housing discrimination, among countless others—there was a mass exodus of white people from the city proper. This wave of suburban migration often dubbed, “white flight”, continued through the 1970s at an exponentially faster pace. To try to capture the true gravity of this exodus in order to better understand its far reaching implications on policing in Detroit we created a sliding map to show the evolution of the city’s racial demographic between 1970 and 1980. This map in conjunction with the ruling in a monumental U.S. Supreme Court case outlined below provides particularly useful context for understanding the environment armed officers were being introduced to and who they were tasked to discipline punitively.

There is a common misconception that public schools in the south tend to be more segregated than those farther north because of the legacy of Jim Crow segregation. Schools in the south may have been more segregated before Brown v. Board (1954), Brown II (1955), and the 1964 Civil Rights Act—the often unsung, yet true catalyst for widespread school integration below the Mason Dixon Line. However, following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Milliken v. Bradley (1974) public schools in the north have quietly become much more racially segregated than their southern counterparts. The majority in Milliken held that a school district bears no obligation to actively pursue desegregation as long as the boundary lines were not drawn with deliberate racist intent. The tragic ramifications of this dangerously weak and broad holding are numerous and will be addressed in relation to Detroit schools below. First however, the reason for the heightened rates of segregation in northern states can be explained by a bizarre phenomenon. In the south the borders of school districts are typically formed in accordance with county lines, but in northern states they are not. This dynamic is complicated but it likely stems from the fact that the municipal power in the south is held by the counties, whereas in northern states, like Michigan, cities and townships—of which there are a great many more of— hold a great deal of the fiscal and political autonomy possessed by local government bodies. In the north these many smaller municipalities often each want their own school district. So as a result, there are for instance, 83 counties in Michigan and 120 counties in Kentucky. However, there are 587 school districts in Michigan and only 129 in Kentucky. Although Michigan has almost twice the amount of people as Kentucky it has nearly five times the number of school districts. Since Milliken abolished inter-district busing, states in the north like Michigan have more racially homogeneous classrooms than Kentucky and its southern peers.

Milliken is not a particularly infamous case in the history of American jurisprudence. Outside of legal academia its not often mentioned among the Court’s most calamitous holdings. The court’s act of profound cowardice cannot be understated and cannot be forgotten. The decision is sickeningly shameful with the benefit of historical hindsight but was undeniably wrong—given its break from the court’s recent precedent. The majority ruling in was an act of spineless deference to the snarling fangs of our country’s most racist malignancies. Governor Milliken and his allies in the white suburbs of Detroit wanted to ensure that the society we all live in continued to be built for white people, even if it had to lay on the foundation of immense suffering of African-Americans. The criminalization of black students by police in schools was undoubtedly exacerbated by Milliken and the ensuing end of inter-district busing. While the school district boundary lines may not have been drawn in a way that equated to explicit de jure racism, the power of many de facto racist policies allowed them to function as a racial dividing line. The state government refused to draw school districts that pulled students from the predominantly black city and the increasingly white suburbs. As a result of many disadvantages such as generational wealth inequality and employment discrimination most black people had no choice but to live in the cheaper, urban areas and send their kids to the underfunded public schools. Even in cases where black people had more financial autonomy they were unable to move into white neighborhoods as a result of redlining—a racist practice of refusing loans to people of color in designated white neighborhoods, regardless of the applicants financial qualifications. After Milliken, the city's hands were tied in a sense. In 1975 they began busing the few white students that there were around the district in order to create as much diversity as possible. But the fact remains that there were no police in suburban white schools like there were in Detroit. While that drastic punitive measure seemed to many to be necessary at the time, this was a totemic decision for Young's mayoralty marking his decision to try to quell crime through aggressive use of the city's law enforcement apparatus as opposed to rehabilitative programs aimed to remedy the underlying causes for the ubiquitous poverty and the crime it brought with it.

Critics of the policy like the group of attorneys highlighted by the Michigan Chronicle in their piece from early February 1975 argued that deciding to bring police into schools to remedy discipline problems unnecessarily criminalizes children from a very young age and pushes them into the prison system instead of punishing them within the context of the educational system, allowing them to learn from their mistakes free of long-term consequences. The implicit and overt biases carry much more power when those charged with discipline can send you to jail, not simply detention.

At the same time that Young's administration decided to intensify punitive discipline programs targeting youth crime—namely via the introduction of armed officers to schools—it began to cut back on social services it provided for students. In January of 1975 Young fired 35 nurses. A few months later in June, Young decided to abrogate all school dental services. Social services were seemingly put on the backburner while the crime problem was being addressed through punitive measures.

While Young's moves to adress the crime program with law enforcement was met with resounding support from the regional boards, the elimination of social services that came with the reallocation of funds for additional police officers was widely condemned. The same boards that were praising Young's support for police in schools were pleading with him to reinstate the nurses and bring back the dental services. For many of the low income residents of Detroit at the time the medical services provided by the city may have been their only avenue for treatment. The damage done from the abrogation of these services in favor of punitive policing programs was two fold as the students were further criminalized and they lost the kind of essential government support that prevents them from turning to crime in the first place.

Income Level Of Communities Surrounding Northwestern High And Duffield Elementary

To further contextualize the Young administration's approach towards education policy at large and the ramifications his punitive crime control agenda had for communities across Detroit it is helpful to expand the lens even further to examine infrastructure funding across the district. For schools in Detroit he consequences of the reallocation of funds for agressive crime control played out in tragically disparate ways depending on the resources of the surrounding community. This dynamic is evident in two starkly different stories of proposed infrastructure projects in 1975, each only a few months after armed officers were let past the schoolhouse gates.

The above map shows two schools Northwestern High School and Duffield Elementary placed onto a map of the city shaded based on median household income. Per the 1980 census the median household income in Detroit was $34,999. This map shows census tracts shaded specifically based on the number of households whose net income exceeded $30,000. As we can see Duffield Elementary School falls near the border of two of the most affluent census tracts in the city. Whereas, Northwestern High—a school with a student body that was 99.8% black—falls between two of the poorest. The wealth of the surrounding communities, unfortunately, seems to have been the crucial determinant in the success of their respective infrastructure proposals.

When a community member with strong ties to Northwestern High School wrote Mayor Young to ask that the city provide materials to repair dilapidated buildings and add something to the sparse greenery he was met with a cordial, but ultimately unhelpful response. Young explained that while he was happy to support the project as a private citizen, there was nothing he could do in his capacity as a government official. He stressed they simply did not have the funds. If the Northwestern community wanted its school to be repaired it needed to be an entirely privately funded endeavor.

This same approach was taken in the case of Duffield Elementary. The crucial difference was that the school has enough private support to fund the project. When the school wanted to clear out area for the construction of a small farm they were able to as a result of funding from a local realty firm, Amuricon.

When public money was spent on police at the expense of social services and infrastructure repair the inequalities that already existed were exacerbated. The city was no longer able to level the playing field by providing funding for a community that couldn’t afford to foot the construction bill. But of course they were in no position to refuse private funding. So, the rich got richer.