Patterns of Police Misconduct

The maps of incidents of police violence or misconduct depicted below reveal important truths about police conduct in the early 1990s. Mapping police misconduct by income shows a concentration of incidents in neighborhoods that were near the median income in Detroit. With a few outliers, these incidents were likely reported because the people who witnessed them were surprised and angered that police could act in such a manner. In reality, it is likely that many more incidents were not reported that occurred in lower-income areas. This could be a result of lack of means or knowledge of how to report police misconduct or simply being desensitized because of the sheer volume of police violence in certain neighborhoods. Small instances of violence may have seemed trivial compared to the homicides that they experienced so often. The map based on income level demonstrates a greater likelihood to report in more affluent areas, but the map based on race shows that almost all of the incidents occurred in areas that were majority African American. The apparent ring around less affluent areas disappears in this map, where even those incidents that are not in primarily African American neighborhoods are very close to them. There is an apparent gap around the Hamtramck area, which is majority white during this period. This provides strong evidence for the hypothesis that police violence was primarily directed towards young African American males. Even though Hamtramck is near downtown, its racial composition spared it from rampant police violence. Primarily African American neighborhoods did not have the same luck.

Most instances of police violence were said to have been prompted by a civilian threatening the life of another person, whether it be the officer that committed the misconduct or another civilian. Trends include officers sexually assaulting civilians, shootings, improper or unwarranted searches, verbal abuse, physical assault, larceny, and drug charges. The victims of these crimes were most commonly young African American males, but there were also multiple instances of domestic abuse of an officer of his or her partner and verbal abuse of other civilians. In multiple instances, officers stole from civilians that they had apprehended or from drug raids that they had conducted. Situations that often prompted these instances of violence included drug raids, routine traffic stops, and when a civilian was suspected of having recently committed a crime. In order for officers to justify their actions, they often claimed that their lives were in danger because of a supposed weapon or because the civilian had fought them physically. While the theme of over-policing was common, under-policing was reported to Mayor Coleman Young and the police department at an alarming rate. Citizens claimed that they would call the police who would take too long to arrive or never come at all. These reports were principally in lower-income neighborhoods. It is likely that the police did not care to respond to the call or that they simply were not convinced that it was an emergency. Throughout the many incidents that we found, a wide range of types were reported, but there were almost none that did not resemble a pattern found within the data.

Police Misconduct and Brutality Incidents (1990-1993)

We located instances of police violence and misconduct through a variety of channels. The primary source was the Coleman Young Papers at the Walter P. Reuther Library and at the Burton Historical Library in Detroit. Civilians wrote letters to Young expressing their concerns about police misconduct, and oftentimes letters that had been sent to the police chief were found in Young’s papers as well. A large percentage of these were written by family members of those who were abused or witnesses of the event. Some were even sent by lawyers of the victims requesting more information. Most letters contained an element of frustration about the lack of discipline taken against officers who had violated department policies. Local newspapers rarely reported on instances of police violence unless they were fatal or had important underlying racial implications. Therefore, we had to rely on letters from citizens and documents from within the police department. From within the DPD, we discovered instances of police violence mainly through the Board of Police Commissioner minutes. The Board of Police Commissioners was established by Mayor Young, and he originally had hoped that it would be a civilian review board. However, he had to compromise and the result was an internal review board that consisted of officials within the department that decided on disciplinary actions. In many of the reports from the secretary in the minutes of the meetings, there is a short description of an officer’s actions and why they were being reviewed by Internal Affairs. In most cases, there was no disciplinary action taken as an outcome.

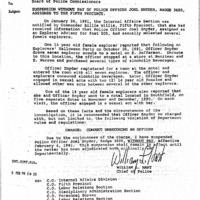

The limited number of sources that we were able to find is a major reason for the limited number of incidents that we were able to uncover. Reporting police violence was skewed for multiple reasons during the early 90s, including the fact that papers may not have been preserved and the police department intentionally did not publicize certain reports. According to an Inter-Office Memorandum, there were 234 shots fired by police from September 1991 until September 1993 that did not result in a homicide. This statistic only includes shots fired, so the number would clearly be higher if it included all types of police violence. There is also no way to tell if this statistic is accurate, as police officers would be unlikely to report a shooting if it reflected poorly on them and there was no way to prove the shooting. Another report from the Internal Controls Bureau stated that there were a total of 78 disciplinary hearings from January to November of 1990. In 1992, the Board of Police Commissioners requested an attorney to work for them that could facilitate appeals hearings, as anyone who was found guilty by the Trial Board was entitled to one. They cited an increasing number of cases and a shortage of staff, which indicates that either officers were becoming more violent or that more people were reporting misconduct. There were over 51 appeals in 1992, which means that at least 51 officers were found guilty by the Trial Board. The number of incidents of police violence and misconduct is impossible to estimate, but it is certainly higher than what is included in the memorandum. We have only identified a small portion of these instances due to restrictions in the collection and recovery of data, but the patterns that we have discovered expose important patterns in police violence.

Sexual Misconduct of Officer Joel Snyder

Officer Joel Snyder was found to have molested two 14-year-old girls while employed as a Detroit police officer. The DPD had a program at the time called “Explorers,” which was created for youth who had an interest in becoming involved with law enforcement in their careers. The program still exists today, and is geared towards adolescents from 14 to 20 years old. Being involved with the explorers gave Snyder direct access to youth whom he manipulated and molested. After a Halloween party for the explorers in 1990, Snyder was said to have brought seven explorers to a motel room that he had rented after dropping some attendees of the party at their homes in a DPD van. He transferred seven youth to his personal vehicle. On the way to the motel he picked up condoms and alcohol which the youth drank at the motel. In the motel, he allowed and even encouraged the explorers to engage in sexual acts with each other and he engaged in sexual acts with two of the explorers. One of the girls that he exploited reported that Snyder had taken her to a motel on five other occasions on which he engaged in sexual intercourse with her.

Snyder was suspended without pay after his actions were reported to the department. The incidents were not reported until three months after they occurred, and Snyder was not suspended until about a week after the report. In 1986, Snyder was accused of taking bribes from a Detroit man in exchange for overlooking the man’s illegal narcotics activity. In 1990, he received honors for outstanding community service from the Detroit Chamber of Commerce and the Detroit Police Department. Reverend Michael Cunningham of the East Lake Baptist Church claimed that he had reported Snyder a year before these incidents for sexual abuse and was assured that it would be taken care of. When Snyder was finally suspended, it was a result of Rev. Cunningham and some Explorers reporting the misconduct directly to Internal Affairs. An article in the Detroit Free Press engages in implicit victim-blaming, accusing the girls of not being “fully aware of the implications of their actions.” This suggests that the girls could have avoided being abused if they had acted in a different manner, and it removes blame from Officer Snyder. Snyder was removed from the police course but it is not clear if any further legal action was taken.

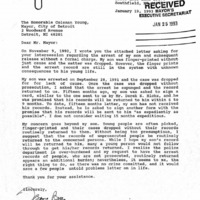

False Arrest of Tessema Berga's Son

On September 28, 1991, a young boy was arrested, but the charges were later dropped for lack of cause. Before the police established just cause, they fingerprinted the boy and entered his arrest records into the internal system. Shortly after this false arrest, the young man and his mother, Tessema Berga, requested that the arrest record be returned by mail so it would no longer be in the system. Berga’s son signed a release promising that his arrest record would be returned in six to nine months, but 15 months later he had still not received it. He was asked to sign a similar form after filing a complaint. Berga’s main concern about her son’s arrest record is that it would present unwarranted issues for him later in life. She relates this to a wider pattern that she is afraid includes many more young people. She suggests that “the records of unprosecuted people be routinely returned to the concerned persons.” While she acknowledges the already overwhelming amount of work that the police department does, she also believes that this was an injustice being carried out on unsuspecting youth. This one incident may seem trivial in the wake of homicides and shootings, but it lends itself to a broader pattern of police neglect of certain duties.

Shooting of DaVern Riley

On July 25, 1993, an unidentified plainclothes officer shot DaVern Riley outside of his home. He was said to have been holding a shotgun, occasionally firing it, according to police records. Police claim that when they told Riley to drop the gun, he pointed it at them. After the shooting, 250 to 300 people gathered and protested police violence. Witnesses claimed that the police shot Riley without warning, and the atmosphere was said to be so tense that the officers took Riley to the hospital themselves rather than waiting for an ambulance. Riley survived despite being shot in the chest. Police allegedly found a shotgun at the scene. This shooting came shortly after those of Gary Glenn and Jose Iturralde, who were both fatally shot. Protesters as well as the media cited these incidents as causing the incident to receive so much attention.

Sources used for this page:

The Detroit Free Press

The Detroit News

Coleman Young Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Board of Police Commissioner Minutes, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.