Juveniles Prosecuted as Adults

“We recently had a sixteen year-old that we waived to adult court for a crime he committed as a fifteen year-old and received a sentence in excess of 30 years.” - Lieutenant Benny Napoleon, 1993

The preceding sections described a broad criminalization of youth over the period of 1982-1985. The environment of high-profile shootings of youth at schools, school sweeps, the enforcement measures taken against youth on Devil’s Night, and stricter curfew laws over a four year period culminated in a legislative movement to prosecute juveniles accused of violent crimes in adult criminal court. Previously unheard of in the juvenile system, legislators, police, and other public interest groups advocated for “automatic waivers” that would transfer a juvenile to face sentencing in adult court. Advocated for prosecuting juveniles as adults would not find success until 1988, but the push that began in 1985 was a result of the aforementioned violence and police response after 1982. Juveniles today are still subject to automatic waivers in many states today, but it was the era before 1985 that served as a turning point in juvenile justice. The narrative of a youth gang problem combined with the Young administration's downplaying of its severity would continue until the end of the 20th century.

Juvenile Waivers to Adult Criminal Court

1985 served as the last year in which the Michigan Supreme Court defended a juvenile’s right to rehabilitative justice in People v. Dunbar, in which the Court found that Jeffrey Dunbar could not be waived to adult court simply on the seriousness of a crime. Professors Frank E. Vandervort & William E. Ladd described this as the “swan song” of rehabilitative justice for juveniles. Since this case did not occur until 1985, it is likely that waivers were being abused for some time before the case was decided. Finally in 1988, the Michigan legislature amended the juvenile code to allow juveniles between the ages of 15 and 17 to be prosecuted in criminal court if the county prosecutor decided it was necessary. This, although not an automatic waiver, was a “reverse waiver,” which gave the government the power to determine how a juvenile was prosecuted based on the seriousness of the offense. Previously the juvenile judge would decide whether or not said juvenile had a possibility of rehabilitation, or if they should be waived. The 1988 statute gave the adult court the power to decide the merit of juvenile cases and took power away from the juvenile court. Michigan legislators like Representative Michael Bennane attacked the juvenile court’s “mindset,” which they charged to be too lenient to violent offenders. Representative Bennane introduced House Bill 4902 in 1985 with the intention of deterring juvenile offenders with harsher sentencing through automatic waivers. Although it did not pass, he spearheaded the movement for automatic waivers that succeeded in 1996 in People v. Conrat, when the Michigan Supreme Court upheld the automatic waivers statute which made 14 year-old youth eligible to be prosecuted as adults.

Governor Blanchard and Mayor Coleman Young's Plan to Arrest 1,000 Youth

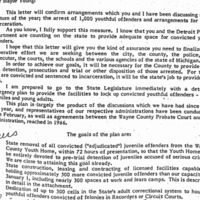

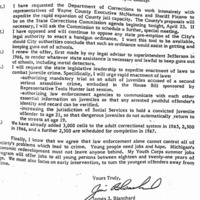

Below are reproduced documents from 1986 showing correspondence from the office of Governor James Blanchard to Coleman Young, outlying a plan to conduct a mass arrest of 1,000 youth; additionally, Governor Blanchard displays his intention to pass automatic waivers through the Michigan legislature, an effort that will finally find success in 1988.

African-American youth are far more likely to be in jail than in a rehabiliatative home -

Alternatives to Mass Incarceration

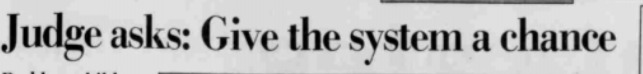

Although much of the administration of the city of Detroit advocated for a crackdown on juveniles, a Wayne county judge, Gladys Barsamian, wrote an aricle for the Detorit Free Press advocating for an alternate to locking up massive amounts of juveniles. She addresses all aspects of the issue starting with that many people do not believe that it is acceptable to incarcerate juveniles at all, including the state of Massachusetts where they have closed their institutions in preference to helping the children improve. The Wayne County judge, Barsamian, argues that families and schools can play a role in reforming juveniles through education and nurturing development. Additionally, Barsamian argues that parents have a large role to play in helping kids improve behavior and that juvenile detention centers are freeing parents of their responsibility to care for their children. Barsamian believes that the community has a large role to play and that community interventions can be very effective at improving juvenile behavior and delinquency.