In-Focus: Racist Violence At Cody High

On the morning of May 29, 1974 violence erupted between hundreds of students who had gathered on Stein Field across the street from Cody High School. Police were called to quell the violence and when the chaos finally subsided they had arrested six students—four white students, charged with felony assault of a police officer, and two black students, charged with inciting a riot. Following the incident, African-American students leveled complaints of police brutality against the responding officers. The event was a breaking point that forced the community to reckon with long held indignation by the neighborhood’s black residents at their mistreatment by police, school officials, and their white neighbors.

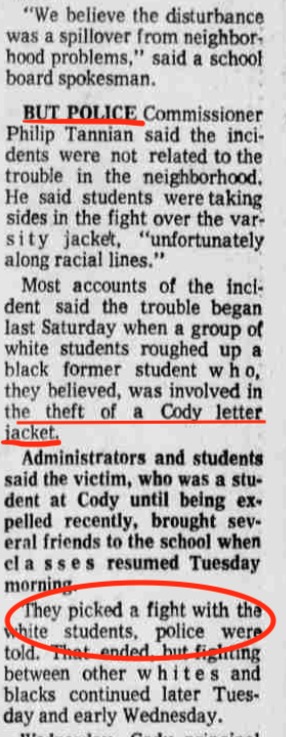

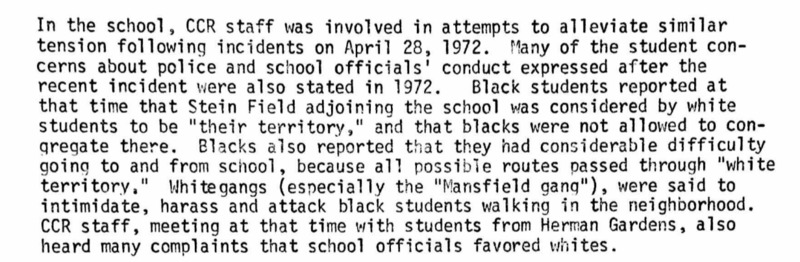

In the Detroit Free Press reporting on the incident a lot is lost. The coverage lacks mention of specific allegations that were extensively documented in the DCCR’s records of the incident but also, and perhaps even more crucially, in terms of the framing of the underlying causes of the violence itself. In its initial reporting of the incident the Free Press gives little credence to the conclusion most supported by the first hand accounts of the incident—that the violence that broke out on May 29th was the result of racial tension in the larger community that had been building for a long time. The article instead asserts that this widespread chaos precipitated rapidly in the aftermath over a fight over a letter jacket between white and black students. The specific catalyst for this event was likely the fight over a letter jacket. But framing this as the cause for the violence that ensued is in profound contradiction with accounts from black students about what a hostile, racist environment Cody High was for years before this particular incident.

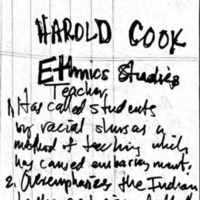

The racist abuse was not solely instigated by students either. The black students alleged that teachers espoused racial prejudice of their own. In notes taken by someone on the Ad Hoc committee detail specific teachers students accused of racist behavior.This history gives context to the debate that exists in the coverage of this event between whether this is an isolated fight between white and black students or the climax of years of racist abuse of black students.

The scene the DCCR records paints is a horrifying departure from the reality described in the Free Press’s accounts of the event. Black students alleged that gangs of white students were beating up smaller groups of black students. The security guard at the school recalled disarming white people armed with clubs and even one with a shotgun. Black students who had fled inside to seek refuge in the lunchroom were then driven out by police officers, who injured some of them in the process. Some African-American students who had taken refuge in the Vice-Principal’s office were injured by glass shards when police shattered the windows and broke in. Later that morning after most of the white crowd had been dispersed by police the black students in the school were released to leave but the police refused to provide escorts outside the school doors.

The allegation that police detained a black student and brought them back to the precinct and beat them is not mentioned in any of the newspaper articles about the incident. There is no mention of the name “Leslie Mambors” in any of the Detroit Free Press or Detroit News databases following this incident. It is difficult to say with certainty why this is. It is possible that this allegation was unsubstantiated and therefore was quickly dismissed by reporters covering the story. However, given the way that these mainstream newspapers belie a litany of allegations of police violence against African-Americans in their reporting of this incident, it appears the absence of this particular accusation is indicative of a concerted effort to frame the events in a way that portrays police as the saviors not the aggressors. This omission also speaks to the difficulty of filing complaints against police that will be deemed worthy of a serious reaction from the city and coverage from the media. Without family money or the backing of a powerful community organization it was nearly impossible to mount a complaint that could gain any traction. As a result, many instances of police violence are lost from the public record, existing only as memories in the minds of those most deserving of recompense but too powerless to ever hope to receive it.

There was a huge debate in the community about whether or not to keep the school open the next day. Dr. Jefferson, the region 3 superintendent refused to close the school despite huge pressure from black parents who felt that there needed to be an investigation before they felt safe sending their kids back to class. The school reopened on Friday with a heavy police presence. Only 20% of students attended class that day.

In the aftermath of the events an ad hoc committee was formed with parents, school employees, and community members to investigate the events of late May 1974 and the larger context that led up to the violence. This committee worked in conjunction with local community organizations such as the Far West to create community workshops to increase racial sensitivity and decrease hostility.