Livernois 5

The Livernois 5 incident marks three days of confrontation between the Livernois-Fenkell community and the DPD during the summer of 1975. Over the course of the three days, two people were killed — 18-year-old Obie Wynn, and an older gentleman Marian Pyszko. Obie Wynn was shot by Andrew Chinarian and due to the lack of justice for Wynn, the community organized and took to the street. As Marian was driving home from work and in the chaos of protest, he suffered fatal injuries inflicted by unidentified protestors. It was the death of Marian Psyzko that led to a “racist dragnet” of arrests. Any young black man that could be pinned to the area was arrested. Eventually, the DPD had their “Livernois 5:” Raymond Peoples, James Henderson, Ronald Jordan, George Young and Douglas Lane. Through three separate trials and eleven months in custody, they were all eventually released and acquitted. The incident marks the first substantial test of Coleman Young’s “people’s police department” and his commitment to “law and order, with justice.”

Three Days of Confrontation

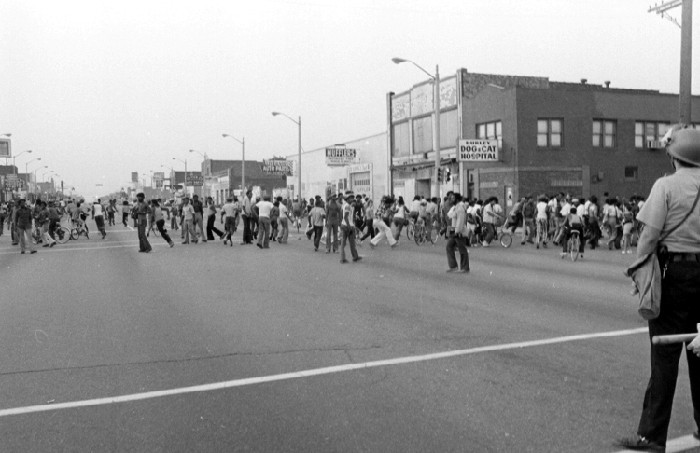

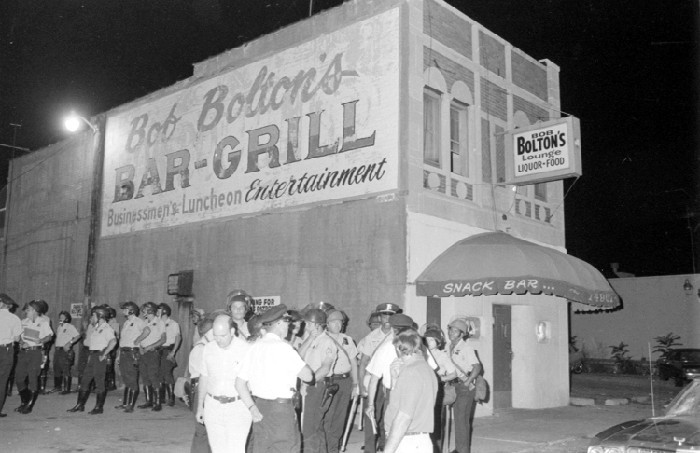

At around 8pm on July 28, 1975, 18-year-old Obie Wynn was shot in the back of the head by a white bar owner, Andrew Chinarian. The incident took place in the parking lot of Chinarian’s establishment, Bolton’s Bar. Chinarian was taken into questioning but promptly released. The Livernois-Fenkell neighborhood demanded justice. Groups of protesters were throwing stones at officers and passing cars. Unfortunately, Marion Psyzko’s car radio was broken and he was unaware of the protests occuring along his route home. When he stopped at a light he was pulled from his car and beaten, and taken to the hospital in critical condition. He was the only person that required critical care as a result of the anger. Protesters were active late into the evening and around 3 am Coleman Young faced the crowd claiming that “it was a terrible mistake to release that man (Chinarian)” and assured the crowd there would be justice. Tear gas was used in order to break up the crowd and according to one account, sixty three people were arrested on this night alone.

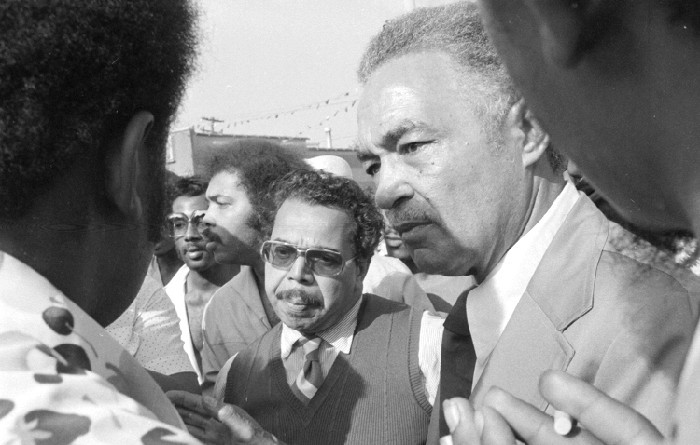

The following morning, Chinarian was arrested and charged with second-degree murder. Mayor Young and Chief Tannian held a press conference in order to announce the arrest in hopes of quelling community outrage. However, the Recorder’s Court Judge Donald Leonard set the bond at $500 and within two hours the bond was posted and Chinarian left again. This infuriated the community. People have been held for loitering for $500. By sunset, an organized mass of protesters around 300 strong was confronted by nearly 100 officers. One group attempted to use a car as a battering ram to break down the bar door. After hearing this, Mayor Young came to the scene, standing on the hood of that same vehicle and attempted an appeal to the crowd. He spoke out against the bond as being set too low as he tried to convince the angry citizens that he heard them, and was on their side. Mayor Young urged the crowd to not destroy their own community in their effort to fight for its youth.

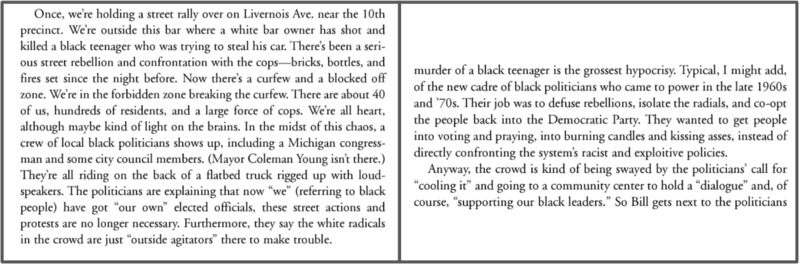

According to one leftist activist, William Gilbreth, Young was not the only black figurehead attempting to assuage the crowd’s anger. Several black politicians were there, addressing the black community and demanding that they leave the streets. They claimed that their rise to elected positions of power meant protests were no longer necessary. Radicals were being called out and the people were being urged to pray and vote their way to justice instead of “directly confronting the system’s racist and exploitative policies.” Gilbreth was not alone in his distrust of trying to vote a society just. There were two belief systems at work, divided largely along class lines. For the upwardly mobile black community, successfully electing black people to positions of power marked a huge success for the civil rights struggle of the decades prior. The work was more or less over and they felt comfortable following the system’s channels of voting and complaint filing to see their needs met. With black people in power, their voices felt heard and the system worked better for them. They were more easily soothed by the appeals made on that Tuesday evening. However, in lower and working class neighborhoods, life remained brutal. Black people of this socioeconomic status were continuously overpoliced and subsequently brutalized. As noted in the section on complaints (link), the impoverished black communities are less likely to participate in the democratic system. While there are many factors that contribute to this, one is the continued failure of the system to bring justice to this community. They likely feel ignored by government officials, regardless of racial identity.

As such, the looting continued despite appeals. Policemen touting full riot armor swept through the crowd with tear gas. Forty-three more people were arrested on Tuesday night, the total now at 96. According to one report, some of the protesters were released on a $500 bond, the same as Chinarian’s. The violence by protesters remained contained to the Livernois-Fenkell area. The papers report community cooperation and the active presence of Coleman Young as the key components to containing the incident and its relatively rapid de-escalation. By Wednesday, peace had returned to the neighborhood but a heavy police presence remained. On Tuesday night, Young had reportedly advised Tannian to deploy as many black officers as the department could spare in the hopes that it would change protesters’ perception of the department. Young hoped that establishing cooperation between the civic, community, and church groups with the police would minimize violence. The political leaders Gilbreth wrote about were among Mayor Young’s “peacekeepers.” Mayor Young gathered black leaders from the political realm as well as from the local churches in order to serve as an intermediary force between the demonstrators and the police.

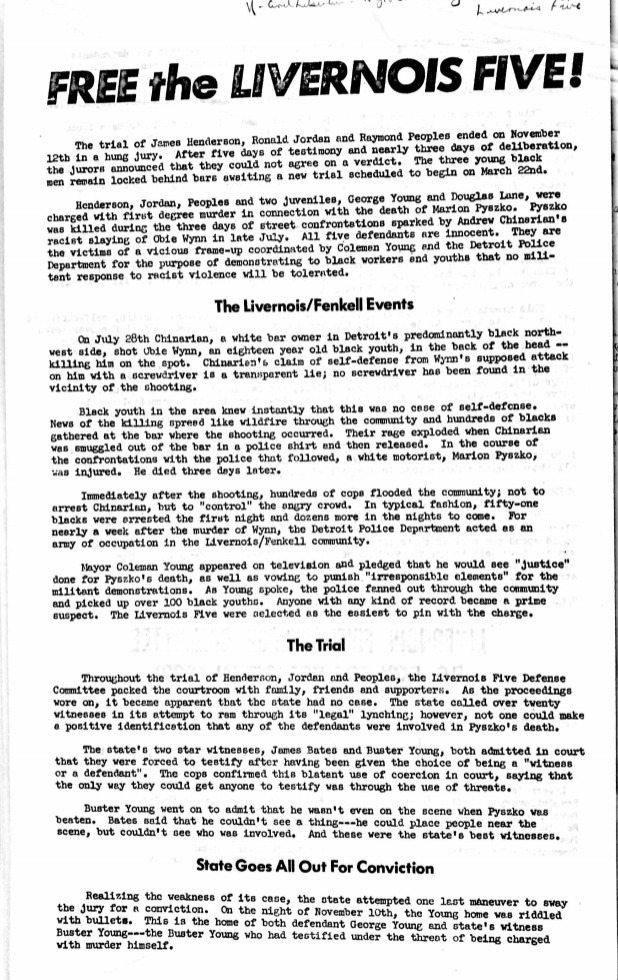

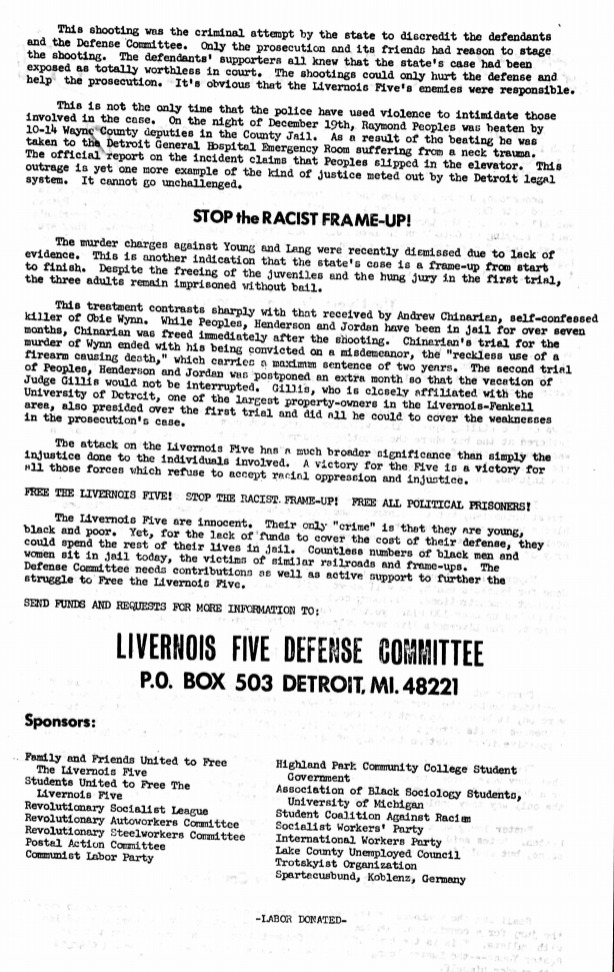

By July 30, it was announced that Marian Pyszko had passed. After the mass arrests and using coercion, Pyszko’s death was pinned on six young black men: Raymond Peoples, James Henderson, Ronald Jordan, George Young, Douglas Lane and Dennis Lindsay. They were arrested and held without bail in the Wayne County Jail as they awaited trial. The six were held without witnesses that could undoubtedly testify to their involvement. The six men were allegedly in the area at the time and had minor confrontations with police in the past. As a result, they were the six easiest targets for the Police Department. Dennis Lindsay was promptly released and his charges were dropped due to the efforts of his attorney, Kenneth Cockrel. Unfortunately for the other five, Cockrel stopped working on the case once Lindsay’s charges were dropped and they remained in jail and held without bail. The Leftist activist coalition “The Livernois 5 Defense Committee” called their arrests a “frame-up” and demanded justice for the young men. The Committee worked tirelessly throughout the trial and the marxist newspaper, “The Torch” accredits much of the eventual acquittal to the Committee’s efforts.

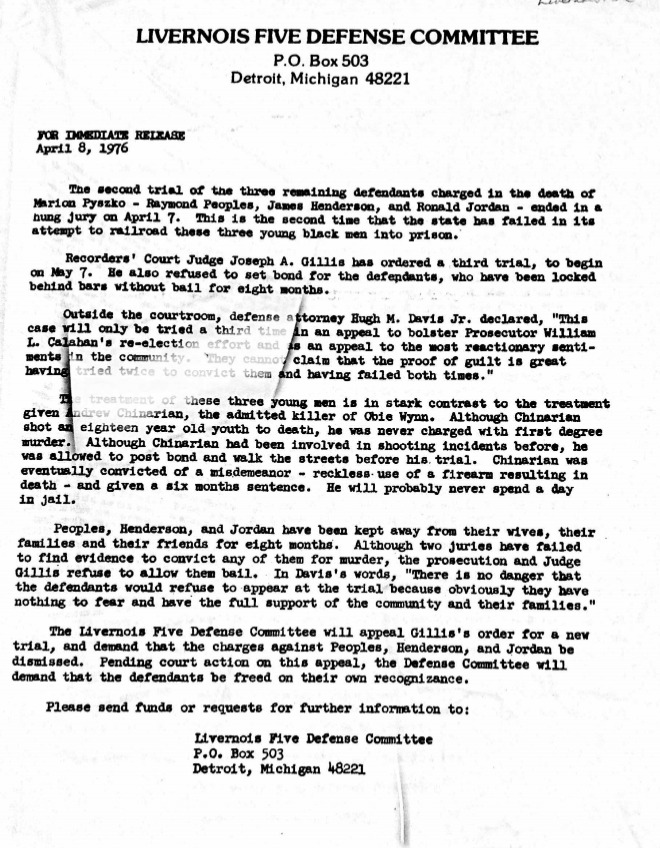

The white bar owner Chinarian was undeniably guilty and eventually held at a twenty-five thousand dollar bond, though the bond was still posted the same day. Chinarian was able to reopen his bar three months later while he awaited trial. The Livernois Five were denied bail repeatedly by Judge Gillis. Peoples, Henderson, and Jordan endured abuse by officers while they were kept away from their lives and families for eleven months. The financial and psychological impact of such treatment cannot be overstated. This is not an isolated occurrence. The cash bail system, as a tool in the larger criminal justice apparatus, is often used to criminalize and coerce the black working class, barring them from work and their familial obligations while those with means walk free.

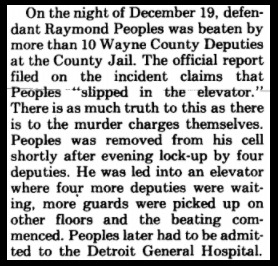

Furthermore, as described by historian Michael Stauch, the Wayne County Jail (WCJ) is a notorious nightmare. According to the progressive Judge Ravitz, “the Wayne county jail is a monstrosity — an overcrowded outmoded disgrace to the county and a daily hell for the prisoners, almost all of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime.” It is rat and cockroach infested, with bad plumbing and cold meals. Officers repeatedly and randomly abused inmates, hidden from the public eye. Within a month of the Livernois 5’s arrival at the WCJ, four African American men had died in police custody. In December, after five months in jail, Peoples was beaten by police and received wounds extensive enough to require medical treatment.

The Livernois 5 Trial

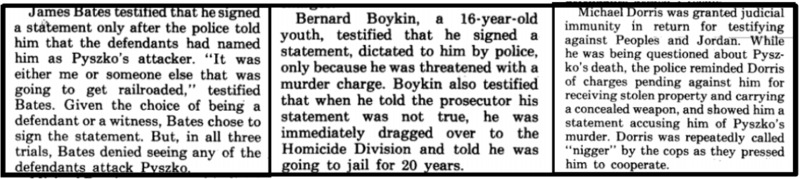

There was a total of three trials before the remaining five were finally released or acquitted. As previously stated, the initial arrest included a sixth young man, Dennis Lindsay but he was promptly released. The first two of the infamous five to be released were the juveniles: Young, and Lane. This was largely due to the lack of evidence and exposed coercion. As previously mentioned the young men were arrested essentially at random and then the prosecution built a case through intimidating and threatening viable witnesses. Officers offered to clear records for statements that connected the convicted to the crime. For example, Michael Dorris was a witness in the case against Dennis Lindsay and Ronald Jordan. Dorris, who shared a cell with Lindsay and Jordan after the mass arrests, received immunity for pending car theft and concealed weapon charges in exchange for identifying the defendants. Dorris later testified that he was afraid of receiving a 10 year sentence if he failed to participate in the collusion. Furthermore, Jimmy Bates originally agreed to testify and identify Peoples, Jordan, and Henderson assaulting Psyzko. However, according to the Michigan Chronicle, his involvement was only after police investigators gave him “the choice of being either a defendant or a witness in the case.”

The first trial ended in a hung jury, and the second trial was much of the same. A mistrial was declared and the prosecution declared its intention to seek another trial which was fought by the defense. The third trial was set for May 7, 1976. It was not until the third trail when the defense was able to expose the extent of the collusion. The young men were acquitted, their charges dropped, and they were free. In The Torch the final trial is celebrated as a victory for the Black working class and most notably “The Livernois Five Defense Committee.” In spite of the injustices throughout the entire event and trail, the Livernois Five and their supporters fought back and won. Their victory does not overshadow the prolonged impact on the young men’s psyches, families, or the financial burden of the trial. It is a victory to celebrate nonetheless.

The Livernois 5, particularly Jordan, Henderson, and Peoples, were pursued by law enforcement with a ferocity completely unknown to Chinarian. In the words of an angry citizen, “Although Chinarian shot an eighteen year old to death he was never charged with first degree murder. Although Chinarian had been involved in shooting incidents before, he was allowed to post bond and walk the streets before his trial.” The bar owner was eventually convicted of reckless use of a firearm resulting in death — a misdemeanor —and a 6 month sentence. The article continues, “He will likely never spend a day in jail,” and he did not.

Activist Response

An organized activist effort responded to the mass arrests and racist discrepancy in the treatment of Chinarian versus the Livernois Five. The “Livernois Five Defense Committee” emerged as a coalition of radical activist networks. Their primary objective was to raise funds for the defendants and awareness surrounding the injustices of the case. It should be noted that this level of a documented and organized response was relatively rare in the 70s. Radicals were focused on labor movements. Furthermore, according to Gilbreth, there was less social capital to be gained for attending protests in this era in comparison to the decade prior. In turn, activist efforts were no longer publicized as heroic mass movements but rather disruptive and frivolous riots. As such, protesting was equated to “making a fuss” instead of a constitutional right to pursue justice. The Torch considered the trial an act of criminalizing protest and silencing dissent. The Livernois- Fenkell demonstrators were arguably fighting for justice. One of the Livernois Five men, George Young, defended his presence at the protest. In his testimony, he expressed that he was taking a stand against a criminal justice apparatus that prioritized white comfort over black lives.

The Torch accredits much of the trial’s eventual success to the Defense Committee’s persistent efforts. The Livernois Five Defense Committee worked tirelessly to expose the coercion and alleviate the financial burden accumulated over the three trials. Instead of heroizing Mayor Young like the Free Press and Detroit News, the Defense Committee and the Torch illustrated the shortcomings of liberal reform. For the Black working class, identity politics do not suffice. While representation in positions of power is a crucial step, systemic racism and capitalism continued to be an oppressive force.

Andrew Chinarian and Vigilante Justice

The Detroit Free Press ran an editorial piece highlighting Chinarian and his status as the neighborhood “protector.” While simultaneously in another piece on the same page the author condemned the black community for not “just allowing things to pass through the legal system.” When the black community demands justice via protest it is classified as a “senseless riot” but a white man is justified in shooting and killing a young black man for an alleged attempted robbery. It’s important to point out that the media scolded the Livernois 5 for not letting the police officers take care of Obie Wynn’s death. Journalists chose to highlight Chinarian’s history of taking “justice into his own hands,” and failed to consider that Chinarian himself could have waited and called police to handle the situation. Given the continued history of police brutality, police may not have been any less violent. Rather, the example serves to highlight the hypocrisy within the media. Through the editorial, white journalists justified the white bar owner’s violence as a defense of property. In the same issue, the same journalists reprimanded the Livernois-Fenkell community for demanding justice for their murdered youth.

Chinarian’s neighbors were eager to share his valiant history of “showing up” to check up on any potential “danger.” He has a record of armed violence which was provided in the article as proof that he was there to “protect.” He was a valued business owner that was heroized for vigilante justice.

This rise of vigilante justice may stem from Coleman Young’s push for a “people's police force.” In a context that encourages community involvement in policing, citizens are emboldened to take law enforcement into their own hands as untrained officers but armed all the same. They may feel like they are “helping” the department by participating in the “crime-fighting efforts.” The prevailing ideology remained that an increased police presence would inherently reduce crime. In turn, wherever police were not, crime thrived. We know now this to be false, however it is from this line of thought that preemptive programs such as STRESS emerged. STRESS placed undercover cops throughout Detroit seeking conflict in order to make arrests and separate potentially “dangerous” people from the rest of society. [For more on STRESS, click here]. Similarly, neighborhood watch efforts increased throughout the 70s and were celebrated by the department. The neighborhood watch programs are akin to a citizen's take on STRESS which can provoke a sense of justified violence in the members as they “keep their neighborhood safe.” Another offshoot of community policing in the context of vigilante justice was the rise of ministations in this era. [For more on ministations click here.]

In the 70s the rise of vigilante justice became increasingly entangled with the police department. Vigilantes, while feeling the support of the Young administration and the DPD via the push for community-involved policing, were often also friends of officers which only solidified their pseudo-cop identity. Chinarian owned Bolton’s Bar — a notorious white-cop hangout in a majority-black neighborhood and the unofficial headquarters for the 10th precinct, off duty. Community members document Chinarian as a hostile presence. He was a racist, and according to a Detroit News editorial, he worked to keep his establishment white-only through a locked door and buzzer. The fact that the 10th precinct chose this bar regularly only further illustrates the racism that defined the department. That said, it was Chinarian’s camaraderie with the precinct that resulted in his swift return to business as usual. Chinarian shot and killed Obie Wynn and yet the Detroit Free Press chose to remember him as a “man defending his property.”

Role of the Media

The majority of the information synthesized on this page is from newspaper research. We attempted to collect information from a range of political perspectives, however, there are inherent silences in what is collected. There were a few books and a dissertation cited to supplement the findings. With the majority of our information stemming from newspaper articles, the impact of their narratives must be pulled apart.

There were no notable differences between the Detroit Free Press or the Detroit News, but rather it was incredibly author-dependent. That said, Obie Wynn was rarely ever mentioned without his list of petty theft charges or run-ins with law enforcement. It was imperative to convey that Wynn was not an innocent kid but rather a delinquent with history. Chinarian at his worst was a white man benefitting from his friendship with officers, and at his best, a “neighborhood protector.” Only in leftist media was he regarded accurately, as a violent racist.

Leftist media framed the trial as an act of criminalizing the pursuit of justice. The Livernois Five were being pinned for murder without substantial witnesses. While a man was killed, all of the young men present that day were arguably fighting for justice. One of the Livernois 5 men, George Young defended his right to be there that day, participating in the protest. He believed he was taking a stand against a criminal justice apparatus that cares far more about white comfort than black lives.

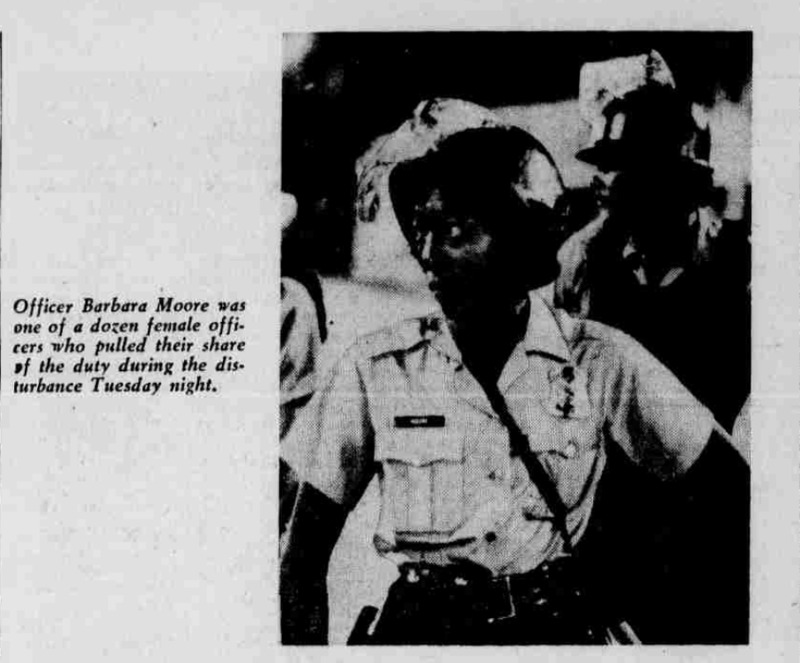

Mainstream media regarded officers as heroes. The papers also capitalized on the incident as a mechanism to celebrate female officers. Coleman Young’s affirmative action policies meant that there were more women recruited to the DPD. Women “proved themselves” by being just as tough (read: violent) and this was celebrated. [Link to team 2 affirmative action]

The media portrayal of celebrating officers mirrors the coverage of the 1967 rebellion. The only difference is the inclusion of the role of the community in reducing the violence. We believe this reflects the emphasis on community policing in Mayor Young’s platform. Thus the community is being celebrated as an added police force — not for community sake but rather as an extension of the DPD. The media encourages the community to be “tough on crime” while effectively criminalizing the fight for justice. The protesters were excluded from “the community” and the protests were framed as a melee in the papers. Journalists blamed the protesters for the disturbance and the consequent mass arrests instead holding the department responsible for a radicalized panic that culminated in tear gas. Those that fought for justice were shunned while those that chose silence were celebrated.

The attempt to celebrate the community and Mayor Young is in part a reluctance to give up on the idealized vision that Young represents. That is, a black man leading a black majority population and doing it successfully. This is particularly true for the upwardly mobile black Detroiters. Young’s mayoral position serves as a culmination of a long battle for civil rights and administrative representation that marked the decades prior. Therefore, “taking to the streets'' was deemed no longer necessary. The Livernois 5 had less support and it was largely a class issue. The image of equality and peace was enough for most upper-middle class black communities while the working and lower class communities continued to suffer and saw little of Mayor Young’s promised improvements.

The emphasis on community and any attempt to silence the injustice done during the trial is also very likely an issue of public image. Violence does not bode well for Detroit’s already fragile national reputation. According to the archives, Mayor Young was frequently concerned with the media representation of Detroit and the reputation that incidents perpetuate. The papers worked to exclude protestors from the otherwise “peace-seeking” community. “Peace” in this case was understood as passivity and it is a powerful and positive buzzword to spur tourism. In Coleman Young’s platform of “Law and Order with Justice” the justice is yet to be seen. Instead, there was far more energy placed in creating a docile or “peaceful” constituency.

Sources for this page:

Ann Arbor Sun, February 25, 1976

Coleman Young, Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Mayor Coleman Young (New York: Viking, 1994), excerpts (pp. 192-194, 204-213)

Detroit Free Press, July 30, 1975

Detroit Free Press, July 31, 1975

Detroit Free Press, August 2, 1975

Detroit Free Press, August 3, 1975

Detroit Free Press, August 5, 1975

Detroit News July 30, 1975

Detroit News July 31, 1975

Detroit News, August 1, 1975

Detroit News, August 3, 1975

Detroit News, September 11, 1975

Detroit News, November 5, 1975

Detroit News, January 22, 1976

Detroit News, June 19, 1976

Gilbreth, William M.. "People in Motion: One Man's Stories of Class Struggle in Detroit 1968-2000." United States: iUniverse, 2001.

Livernois Five Defense Committee, “Free the Livernois Five!” n.d. [early 1976], and Press Release, April 8, 1976, Folder: Civil Liberties - Blacks - Michigan - Detroit – Livernois Five, Subject Vertical Files, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan.

Michigan Chronicle, August 8, 1975

Michigan Chronicle, August 16, 1975

Obie Wynn Killing Media Coverage 1975-76, Kenneth V. and Sheila M. Cockrel Collection, Folder 25, Box 17, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Trost, Cathy L. “Older blacks condemn riot fever in Detroit” Chicago Defender (Daily Edition) (1973-1975); Jul 31, 1975;ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender pg. 11

The Torch/La Antorcha, vol. 2, no. 12, December 15 1975 to January 14, 1976

The Torch/ La Antorcha, vol 3, no, 1, January 15, 1976 to February 14, 1976

The Torch / La Antorcha, vol. 3, no. 7, July 15 to August 14, 1976.

Riots; Detroit; Livernois-Fenkell Area, July 29, 1975, The Virtual Motor City, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University. https://digital.library.wayne.edu/item/wayne:vmc1017

Stauch, Michael “Wildcat of the Streets: Race, Class, and the Punitive Turn in 1970s Detroit,” (Ph.D. Dissertation: Duke University, 2015)