Drug Use in The DPD

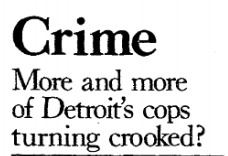

The process of approving and implementing drug testing for the DPD involved an intense back-and-forth between DPD Chief Hart and the DPOA, who opposed the decision vehemently. The fight between Hart (supported by Mayor Young) and the Police Officer's Union went through the summer, with the officers filing a lawsuit against the department for violating their constitutional rights to privacy.

One organization that did support the drug testing of officers was the Detroit Associations of Black Organizations, which penned a letter to Young outlining their support because “even though the questions involved only a few officers, if the police department is to merit and maintain the level of community support it needs, the police department — like Caesar’s wife — must, at all times be above suspicion.” They understand that there may be a constitutional question, but in the circumstances, they believe the risks to be worth the benefits of testing the officers.

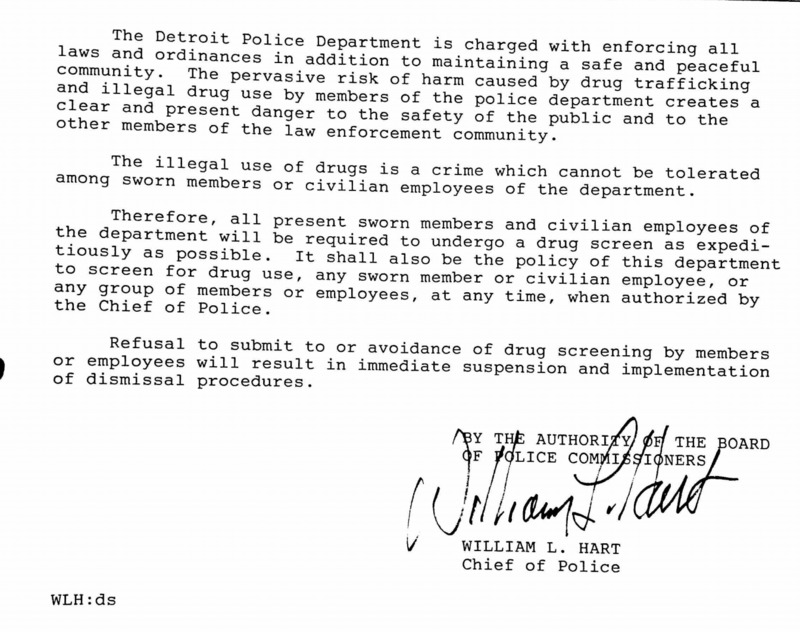

The Board of Police Commissioners disagrees with the claim that there is even a constitutional question to begin with; the question involved in drug testing officers is that of safety and security of the public, and no rights are being infringed upon in their view.

Drug use by Detroit police officers is not a phenomenon limited to this time period. However, with the new allocations of funding going to the DPD to crack down on drug usage in the greater Detroit area, in 1987 and 1988 the question of mandatory drug testing became a major point of contention between the DPOA, Police Chief Hart, and the mayor’s office.

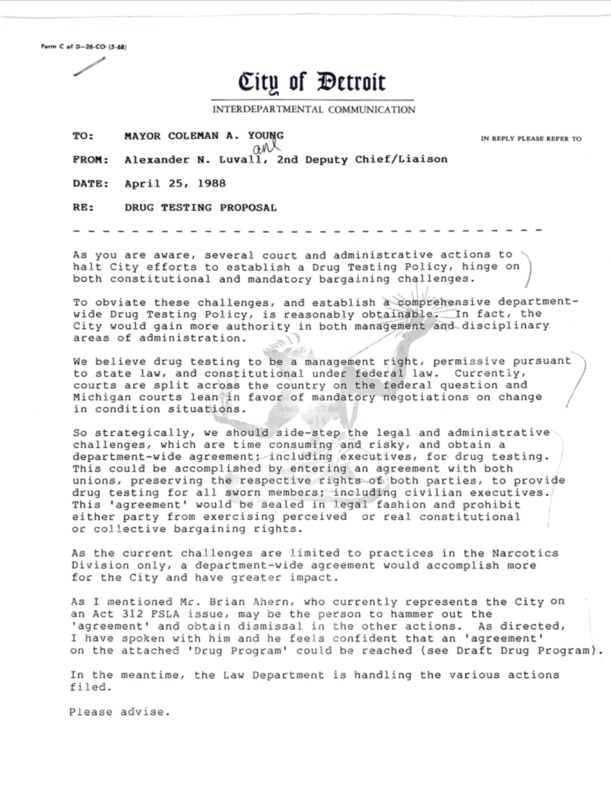

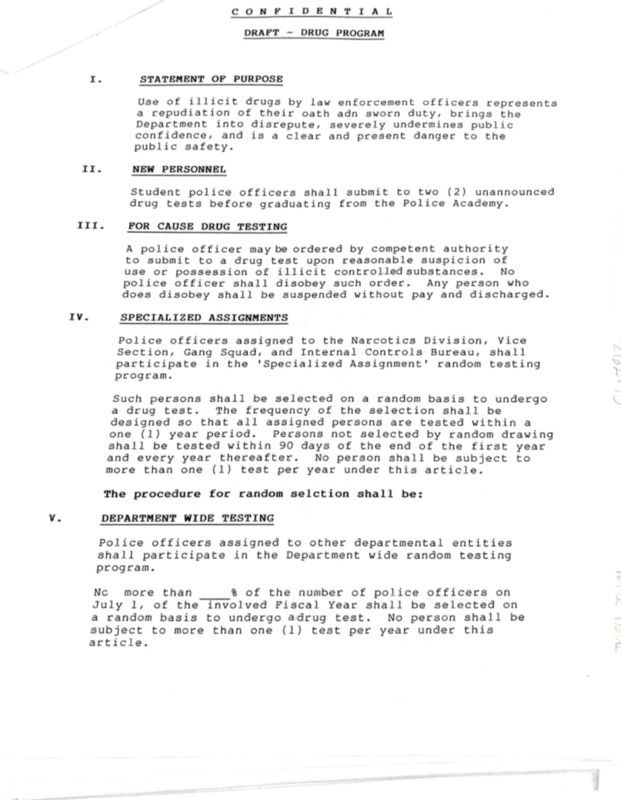

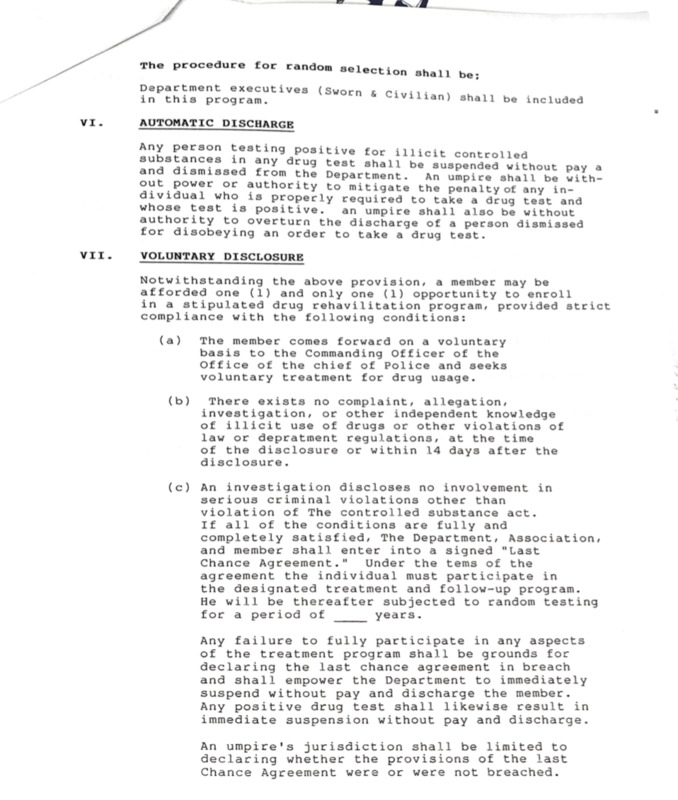

In the spring of 1988, the memos from Mayor Young circulated around the different DPD Precincts; assisted by Chief Hart, the initial order for city-wide mandatory drug testing appeared in May. This caused a riotous reaction from the DPOA, who believed that drug testing was an infringement upon their constitutional rights. The outcry from the DPOA occurred at the same time that reports began to emerge of rampant drug use within the force, ranging from marijuana to crack cocaine to heroin. Reports of incidents of brutality that came at the hands of officers under the influence of narcotics began to emerge within the force and later in the media; the scourge of drug use in Detroit seemed not to be limited to large drug cartels and young Black men whom the police categorized as low-level criminals, but also to the officers themselves.

The use and possession of drugs by DPD officers is a part of a larger area of misconduct surrounding the War on Crack; DPD officers not only were under the influence of drugs while attempting to monitor and police the streets of Detroit, but as well as this, oftentimes these drugs came from the assets seized from suspected, indicted, or convicted drug dealers. Additionally, the DPD’s interaction with drug dealers was not limited to arrests and brutality; in both 1988 and 1989, multiple newspapers detailed the corruption of officers attempting to falsely arrest men for dealing marijuana, and in one case, the officers hired an arsonist to burn down the man’s house.

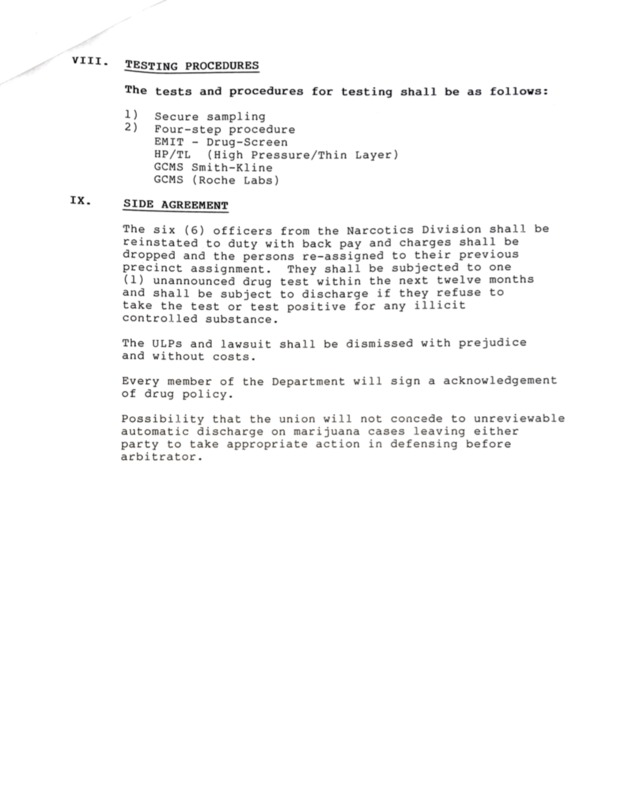

Drug use in the Detroit Police Department was not, judging from reports from both chief Hart as well as the Detroit news media, just a case of a few bad apples; it was a structural and systemic problem within the force that the DPD higher-ups seemingly refused to acknowledge. Officers would be transferred and suspended for short periods of time, but seldom were they dismissed from the force and charged with a crime. The push to drug test the DPD officers which came in 1988 was both long overdue and extremely telling.

The media played a significant role in applying pressure to the DPD to discipline and even dismiss officers who were found to be using narcotics. The Detroit News ran a multi-part series entitled "Cops in Crime" which detailed the use and abuse of drugs by officers while on duty, along with other instances of brutality or misconduct tracked throughout the late 1980s. While the DPD attempted to create the image that the officers found to be using drugs were a small percentile of the force, it was media pressure and investigation which brought awareness to the public that there was a rampant, dangerous trend emerging in the DPD. The effectiveness of this type of journalism during the height of the War on Crack, during which mass panic about the "Crack Epidemic" had already villified drug use in the court of public opinion, is invaluable.

One specific case that was followed doggedly by the Detroit media was officer Steven Allen of the 7th precinct, who was charged with perjury after lying about finding drugs on Dewayne Mancil. Allen, along with another officer of the 7th precinct, filed that they found marijuana on Mancil's person and in his car, whereas an officer of the 12th precinct who witnessed the arrest later testified that there were no drugs present on his person or in his car, but Mancil's wife called in to the police to lead them to drugs in the home because she was mad at her husband. This case dealt not only in the discretionary policing in which officers engaged during this time, but also in the levels of safety which they felt to be comfortable participating in the filing of a false report, along with later perjuring themselves. This was the 2nd reported case of perjury that month for the DPD.

Wark, John T. "Detroit Cop Charged With Perjury" Detroit News. April 8, 1989.

Wark, John T. "Cops in Crime" series. Detroit News. April, 1989.

Draft of Drug Test Policy. Folder 19, Box 262. Coleman A. Young Papers. Burton Historical Library and Archive.

Drug Test Initial Order. General Orders of the Detroit Police Department, 1983-2000, Social Science, Education, and Religion Department, Detroit Public Library.