Citizen Complaints

The City Charter and Reform

The city elected the Detroit Charter Revision Commission on November 3, 1970, with the sole task of drafting the new city charter. The commission was particularly focused on addressing issues of police-community relations and the demand to restructure how the city handled civilian complaints and officer discipline. On July 1st of 1974, the New City Charter established a Board of Police Commissioners. The Commission had been working on its guidelines since the Commission’s inception in 1970. From 1970-1974 the issues of restructuring the department and revamping the methods for handling civilian complaints were heavily contested. [For more on the Board of Police Commissioner’s inception]

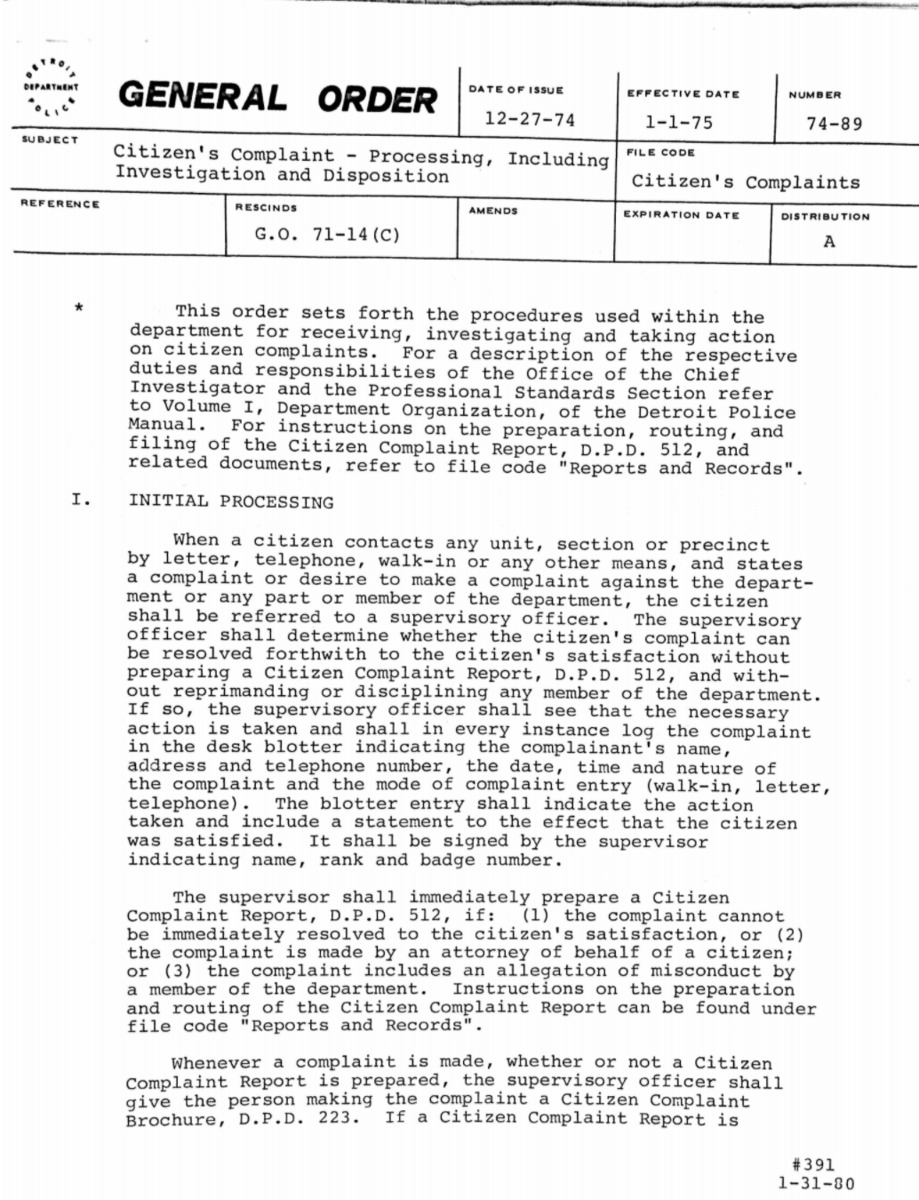

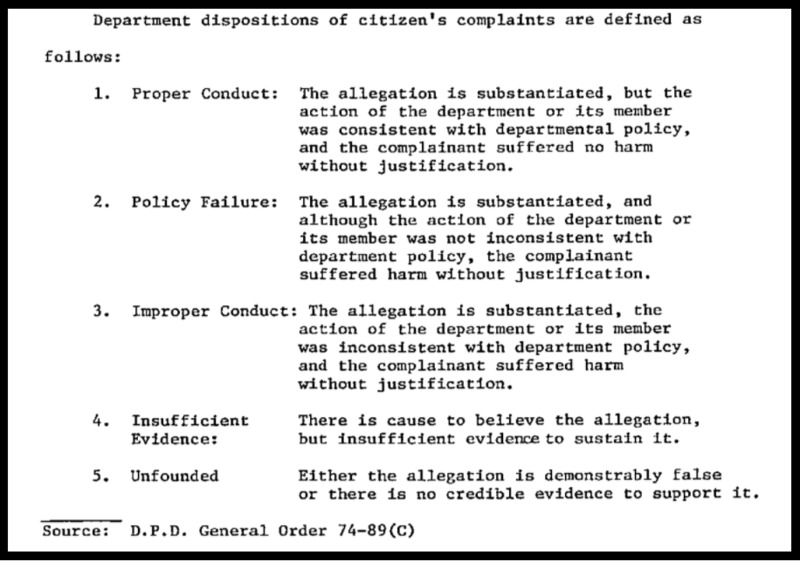

In the 1970 police manual, the entire civilian complaint procedure is simplified to a single paragraph. Essentially, the manual states that complaints are directed to the officer in charge, and “appropriate” action is to be taken by the police department. The police department was made responsible for investigating themselves on a discretionary basis. Such broad discretionary procedures allow for pervasive implicit bias. One effort of the New City Charter Committee was to delineate a more comprehensive policy. Black leaders in particular were advocating for a mechanism of some civilian involvement in police hearings. Police have not been effective at policing themselves. Instead, the “blue line” or the “blue curtain” are terms used to describe officers’ tendency to defend one another. Ike Mckinnon, former Detroit Police Chief, and an officer in the 70s discusses this phenomenon in an interview held at the University of Michigan. (insert audio clip). Another former officer, David Robinson critiques cop culture at length in his memoir.

The “Blue Line”

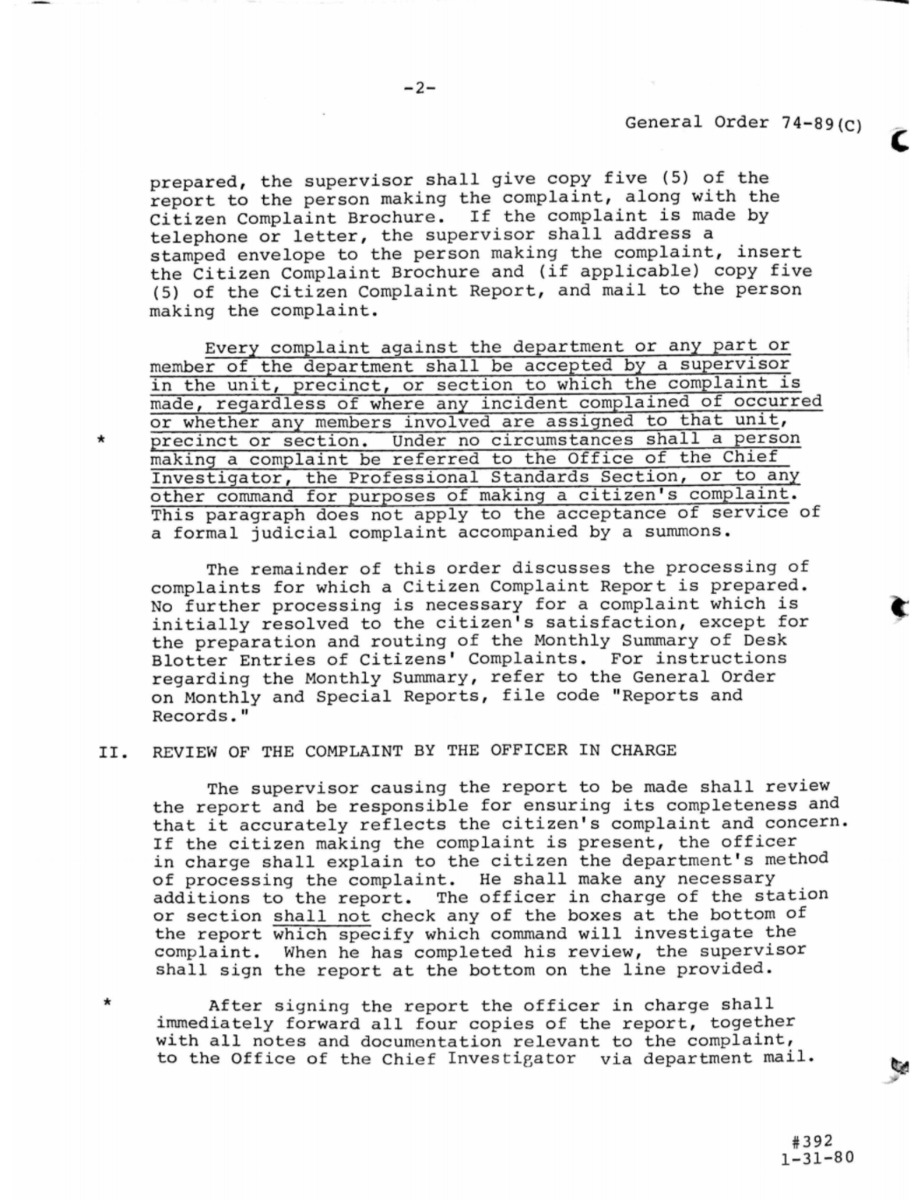

Cops will always defend other cops, and therefore cannot be objective in matters of officer discipline. The “new” complaint procedure allocated all complaint processing to the new “Professional Standards Section” of the Department. The new section is still an offshoot of the larger Detroit Police Department structure, as shown in the graphic. (insert graphic) The section was responsible for conducting and reviewing all investigations concerning citizen complaints. All complaints were handled by the supervisor of whoever took the complaint and it was explicitly stated that this power could not be transferred. Chief Investigator Powell, at a Board of Police Commissioners meeting, expressed his concern over this particular policy and how it left room for an officer that was involved in the incident to have a direct hand in its investigation.

Beyond the initial investigation, the Charter called for the right to appeal to a citizen’s board. The Board of Police Commissioners (BPC) was framed as a citizens board on the technicality that the BPC is composed of citizens. As discussed on this page [link Electing Coleman Young], the citizens were appointed by the Mayor and are majority Black but they are all highly educated, upwardly mobile constituents. The Board of Police Commissioners works very closely with the department and members are not the objective citizens that activists imagined when proposing mechanisms of officer discipline reform.

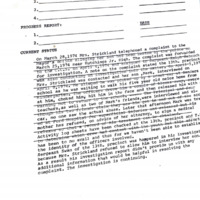

In a memo sent to the Board of Police Commissioners and William Beck Jr, the deputy mayor, the sender vocalized their reservations on allowing officers to handle complaints regardless of the civilian review addendum. Civilians who are making complaints are often victims of police violence, either verbal or physical and in order to make the complaint they must bring it up to the source of this violence. Complainants’ first point of contact is the police. While they do not necessarily have to physically walk into the department, there was a fear of retaliation and further abuse from officers once the complaint is documented. The fear is justified and retaliation from officers is documented, particularly in the form of harassment.

The implicit bias of the department was further evident within the language of the complaint documentation. The reports become slanted in favor of the police. The officer’s perspective is considered a fact against an allegation by the civilian. There can be no system of accountability when the entire case is built up by the same people that cause the initial harm. The memorandum continues to recommend separating the complaint procedures in two categories, with those that deal with police misconduct allocated elsewhere. The result of this memorandum was very little substantive change.

When the complaint is filed and an investigation ensues, there is a slip of paper stapled to the front of the complaint documents where the individual processing the complaint must check off “satisfied” or “unsatisfied.” Some later versions of this slip eventually removed the option to be “unsatisfied.” The only complaints saved in the archives leave a history of allegedly “satisfied” complainants. However, this must be interrogated. There is very little documented action taken by the department. The vast majority of officers received a verbal reprimand or instructed to receive some training. In 1975 there were 2,323 complaints in total and only 11 provoked a civil suit. The process of documenting satisfaction without tangible efforts towards restorative justice creates dangerous pro-cop propaganda. The department published these statistics in order to create the image of a satisfied constituency and improved community-police relations.

An Influx of Citizen’s Complaints

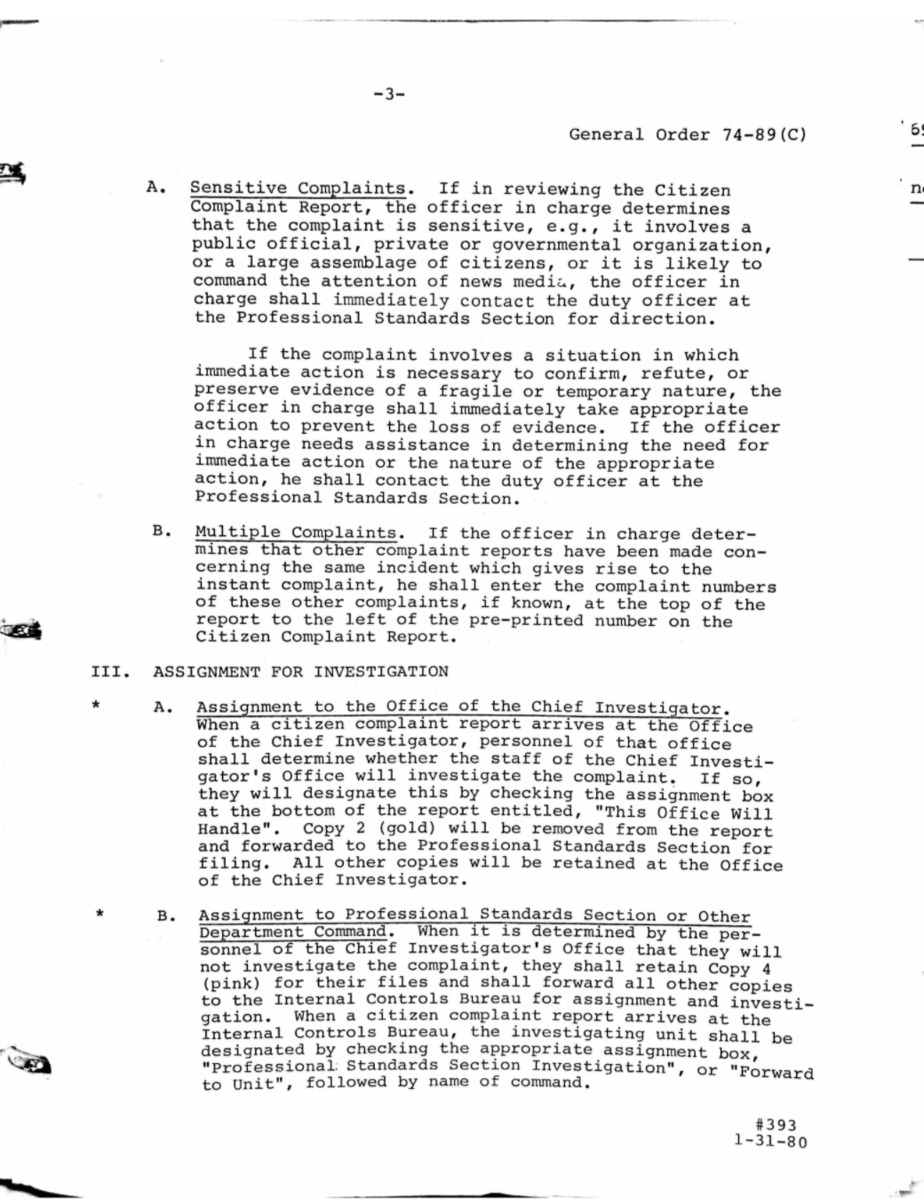

There was a massive influx of citizen’s complaints between 1973 and 1974 with the election of Coleman Young. While it is true that complaint procedures were updated, as previously mentioned, the updates were largely cursory edits that were unlikely the catalyst for this shift. It was more likely a testament to the shift in community perception of the administration, with Mayor Coleman Young at the helm. There seemed to be a surge in hope for police accountability and legitimate justice. In 1974 the department received 1348 complaints, and of these 1230 were regarded as closed, yet only 528 were considered investigated. It is also notable that 1974 had far more complaints in the archives than any other year with 1974-1977 with far more saved complaints than any period after. While there were far more complaints in 1974 than 1977 for example, it is also notable that hundreds more were saved and deemed as important in 1974 than any year after. The collective hope in Mayor Young’s capacity to generate police accountability quickly seemed to fade.

Unfortunately with the influx of complaints, there was little actualized change. The Board of Police Commissioners and the Professional Standards Section were learning and creating structures as complaints came in. Most notably, as previously mentioned, the police were in charge of policing themselves which cannot result in the level of demanded accountability. The absence of legitimate accountability allowed for police brutality to continue at relatively stable rates (link to police violence page). This question of legitimate accountability is a piece of the justification behind abolitionist hesitation to support even civilian oversight boards. The larger societal acculturation of the meanings of justice and criminality must also be dismantled. The ideological facet of ending police brutality is part of the thesis posited by Angela Davis in her work “Are Prisons Obsolete?” as well as a common thread in other abolitionist texts by Mariame Kaba and Ruth Gilmore Wilson.

Complaint Analysis

The following map depicts the locations of the complaints collected from 1974 over the Median Family Income from the 1980 census.

The lighter portions of the map indicate lower-income areas. The most heavily concentrated areas for complaints seem to be along the borders between the lowest income and the subsequent bracket. Large empty patches of the lowest income bracket are not indicative of an absence of police violence, but rather a lack of documented violence. Those that complain had hope that their complaints carried weight. Those with that hope tended to be upwardly mobile. There was and continues to be vast underreporting for all forms of police abuse.

The following map depicts the locations of the complaints collected from 1974 over Racial demographic data from the 1980 census.

Trends

Among the content of the complaints, several trends emerged. Notably, we are only able to analyze what we have access to and these trends may not be entirely indicative of the reality in the early 1970s.

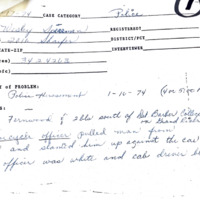

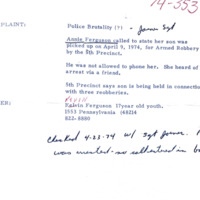

- Women (particularly Black mothers, girlfriends, and wives) submitted complaints regarding police violence on behalf of their sons, boyfriends, husbands and occasionally on behalf of strangers as well

- Normalization of excessive force by officers

- Discretionary Ticketing/Selective Traffic Enforcement

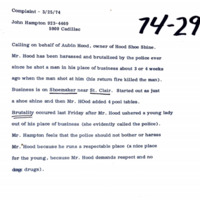

- Armed Break-Ins by Officers

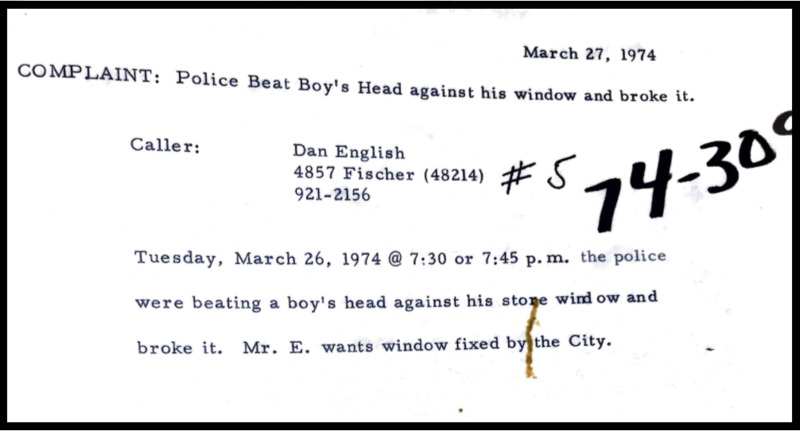

Curtis Jones’s Story: One lens for understanding underreporting is to grasp the normalization of police abuse, particularly in underfunded communities. The following story depicts racist violence and may be triggering. One particularly jarring complaint was filed by a store owner. He called to complain that the police cracked his storefront window as a result of beating a young Black man’s head into it. His concern was not with injury or excessive force used on the young man, later identified as Curtis Jones Jr, but rather demanding the city pay for his broken window. Curtis Jones was allegedly interfering with traffic when the officers attempted to arrest him. Jones resisted and the officers violently beat him until he was subdued. It should be noted that the presented report is entirely from the officer’s perspective which includes Jones’s alleged “verbal abuse” of officers which was more likely an exaggeration in order to justify police use of force. The store owner, Dan English, understood that the property damage was an “accident” and he continued to tell the officers to “consider this case closed.” English bore witness to police abuse and yet remained unaffected. The police behavior was likely regarded as standard procedure, which while devastating is unsurprising. Investigation linked here

Furthermore, without English’s complaint, the assault of Curtis Jones Jr would have gone unknown. This specific complaint further emphasizes the pervasive silence of police brutality and the widespread normalization of police abusing Black citizens. The number of actual incidents is far greater than what has been documented.

Women Filing Complaints on Behalf of Men and Boys. The vast majority of complaints from 1974 show the victims of police brutality are the least likely to complain themselves. Particularly when Black men were the victim, it was their wives, girlfriends, or mothers that filed the official complaint. Using just the 1974 complaints that are accessible in the archives, (Trying to figure out how to numerically represent this /accurately). I believe this could either stem from the fear of retaliation after the complaint is made, and/or patriarchal acculturation. There may have been shame attached to complaining and accepting any label associated with “victim.” As such, it was up to the girlfriends, wives, and mothers to seek justice for their loved ones. “On Behalf of” complaints further illustrate the potential for underreporting. Those that made the report would have to know about the incident, and while many witnessed the event themselves, the phenomenon demonstrates that if a Black man does not have that support system, the incident was likely unreported.

Selective Traffic Enforcement. There were also many complaints involving both selective enforcement and wrongful arrests, especially involving a minor traffic violation (link). Officers would routinely pull over and proceed to ticket Black civilians at a perceived far higher rate than their white neighbors. Arrests ensured if the citizen lacked a license or registration. That said, there were reports of officers either refusing to accept their documentation or destroying it in front of their faces in order to proceed with the arrest and collect bail money. For example, in February of 1974, an unnamed officer stopped Delano Kaigler and the officer not only tore up Kaigler’s registration documents but also confiscated Kaigler’s property.

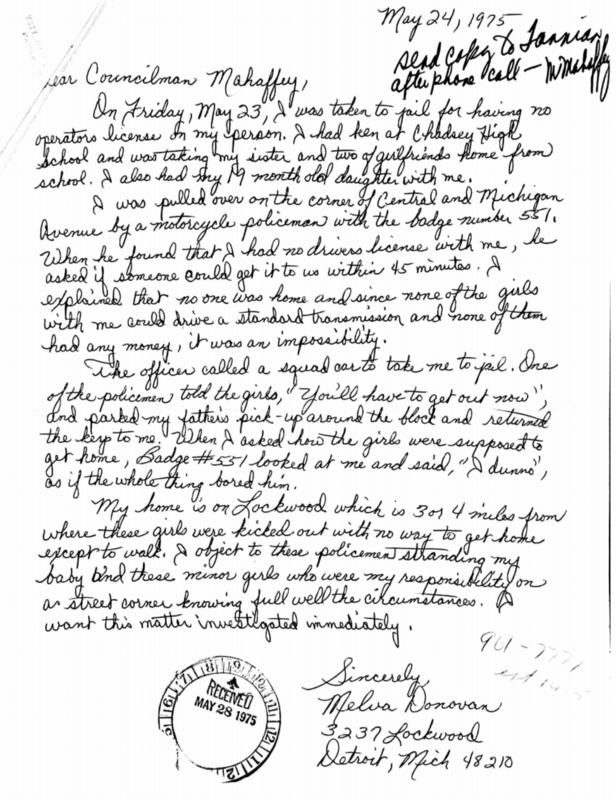

Melva Donovan’s Story: The arrests were often negligent as in the case of Melva Donovan. Donovan was driving her teenage sister and her sister’s two friends home from school in July of 1975. Donovan also had her 19th month old baby on her lap when she was pulled over by Officer Norman Dodson for having five people (including the baby) in the front of the car. Donovan did not have her license on her person nor could she retrieve it within the hour as Officer Dodson requested. Nobody was home at the time and none of the girls knew how to operate a stick shift. Officer Dodson ordered everyone to get out of the car and parked it off the road. He then arrested Donovan and put her in the back of his car to take to the precinct and abandoned the girls with the baby. Officer Dodson, according to Donovan in her complaint, showed no remorse or concern, regardless of the fact that the young girls were 3-4 miles from home with no money. Donovan sent a letter to every councilperson, and a brief investigation followed. Linden Shanks, a sergeant with the traffic section recommended that no action be taken and remarks on the abandonment of the young girls as “unfortunate.” Donovan responded to the apology letter sent by the Board of Police Commissioners. She expressed that her frustrations were solely with the treatment of the girls, not with the arrest and understood the arrest as justified. Donovan was held at the jail for two hour until her husband and father were able to come and post bail. She requested in her follow-up letter that the investigation be reopened. Melva Donovan’s persistence for adequate attention was rare. Very few individuals put forth the effort to complain in the first place, let alone continue to demand justice after initial inadequate action.

Armed Break-Ins by Officers: Armed police had a tendency to break into civilian homes without warrants, and proceed to harass and assault the residents. Often their justification was either a complaint or report that an individual involved in an open case lives there. These break-ins are typically reported to occur in the middle of the night, inciting terror in the residents. There was one case, without any names, where a white landlord reported his Black tenant for owning a gun. According to her complaint, officers proceeded to break into her home with machine guns, terrifying her. She presented the officers with her permit to legally own the gun, and no further action was taken. In another incident, Mrs. King filed a complaint when her neighbor’s home was broken into by officers with their guns drawn on May 2, 1974. Her son Steve Slimms was arrested twice after the date of the complaint. He was arrested once for an armed robbery and once for assault with the intent to murder. The initial arrest was at the same home as the complaint. According to the complaint file, Mrs. King was satisfied once the officers admitted that they should not have had their guns drawn and will not do this to her again.

Stop and Frisk: There were notably very few complaints regarding stop and frisk policies. If there was a complaint, the complainant would state they understood the stop and frisk procedure but the complaint was regarding the stolen property or excessive force. The lack of complaints proves not the absence of abuse but rather the normalization of the discretionary and racist harassment of stop and frisk practices. When it is expected, one is unlikely to complain about it. Complaints are reserved for those that believe, on some level, change will be enacted as a direct result of their complaint. While there was an influx of this hope with the election of Coleman Young, the hope was not equally distributed throughout the city.

Complaint Proceedings Lacked Justice

The vast majority of complaints are ruled as proper procedure. “Innocent until proven guilty” is a grace that was (and continues to be) exclusively reserved for officers and white people with financial means. Black men, especially young Black men were presumed criminals with such adamence that when they fled, they were shot in the back, a capital punishment.

During the Board of Police Commissioners meetings it became evident that the Professional Standards Section could not process the number of complaints within their outlined time parameters, let alone follow through with sufficient investigations. According to the 1976 manual, the department continued to receive an average of 190 complaints a month. In 1974, the complaint procedures were new and they lacked the structure to be successful particularly with the high numbers.

In order to remedy this, the Professional Standards Section worked to recruit and train more investigators. They concluded that 8 weeks of training would be sufficient and the investigators were to be civilian hires that were also required to go on an officer ride-along in order to “remove bias,” and breakdown “excessive sympathy” for the civilian experience. However it could also be concluded that this would instead be a counterintuitive measure that only obscures objectivity by enforcing the same cop-camaraderie. In general, historian John Wesley Donn notes the overwhelming lack of investment in officer instruction that may contribute to the officers’ use of excessive force. Officers were trained for 48 hours on firearms safety and less than 10% were given advanced firearm safety “when to shoot” training. Even with the new investigators, their training is only eight weeks long in order to meet the demand for investigation. That said, increased training has been proven insufficient and does not effectively decrease officer violence against civilians.

A Self Perpetuating System

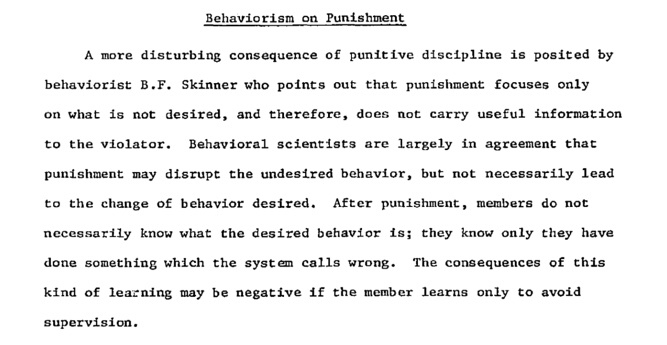

While the New City Charter Commission and the subsequent Board of Police Commissioners redefined and restructured the complaint system, it remained an ineffective mechanism for justice. Nearly every complainant was marked as “satisfied” and yet very few officers were disciplined. Furthermore, as John Wesley Donn asserts, the entire officer disciplinary model failed to change behavior. Officers either took a pay cut or a suspension without any effort to instruct the officer on proper procedure or the impact of their violence. Officers harbored animosity towards civilian complaints which only reinforces the civilian-officer divide — “the Blue Line.” Officer discipline follows a punitive, carceral model. The Carceral system, in all of its appendages, reinforces and propagates violence.

Add here from the 1980 feature on the BPC link

Sources for this page

Annual Statistical Report of Citizen Complaint Investigations, 1975, folder 8, Box 86, Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Citizens Complaints to Detroit Police Department 1974, Boxes 33-35, Coleman A. Young Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

James Lee Anderson and Louis Anderson, Citizen Complaint Report, November 18, 1974, folder 2, box 34, Coleman A. Young Mayoral Papers, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

You see a hero, I see a human being excerpts

Edward Littlejohn; Geneva Smitherman; Alida Quick, "Deadly Force and Its Effects on Police-Community Relations," Howard Law Journal 27, no. 4 (1984): 1131-1184

Deadly force procedures - ncjrs “Use of Deadly Force by Police Officers” Grant no 79-NI-AX-0134 National institute of justice Final report - Arnold Binder, Peter Scharf, Ray Galvin September 1983 Page 163-168

Domm, John Wesley, “Police Performance in the Use of Deadly Force: An Analysis and a Program to Change Decision Premises in the Detroit Police Department”. Doctoral Dissertation, Wayne State University (1981)